From the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Ink Art to auction houses’ selling exhibitions, the art of traditional Chinese ink painting has made a comeback in recent years and the demand is increasing continuously.

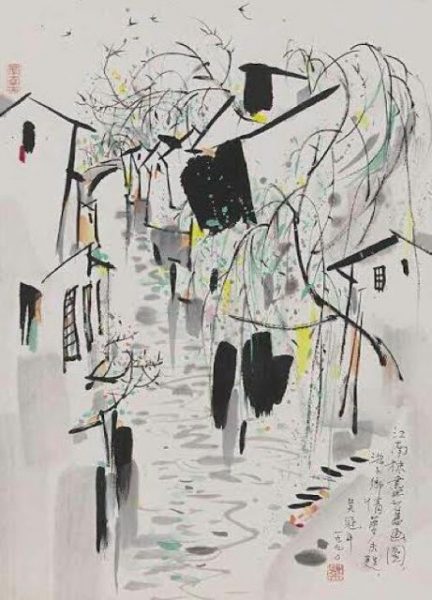

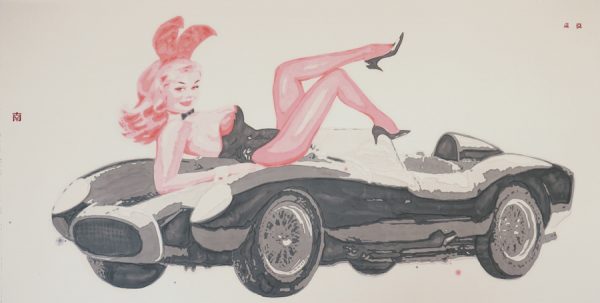

One of the most distinctive mediums of Chinese art, ink painting is grounded in a fine art heritage and aesthetic bedrock dating back more than 1000 years. However, since the early 20th century, with the deepening of Western cultural and artistic influences, it has faded from the contemporary art scene. This occurred in part because ink painting was long ago elevated to the realm of ‘high art,’ and, in the eyes of the leading cognoscenti who determined what constituted good taste, it lacked, in particular, responsiveness to the changing spirit and preferences of the times. As a result, for a period of time, Chinese ink paintings seemed one-dimensional and out of touch with the current visual arts. The fact that the art form was kept alive through the practice of copying the work of earlier masters further weakened its popularity as a form of artistic expression. Today, thanks to the efforts of a group of contemporary artists, Chinese ink painting has shed the rigid constraints of tradition, and now addresses modernity through a revolutionary new artistic language that remains respectful of ancient models.

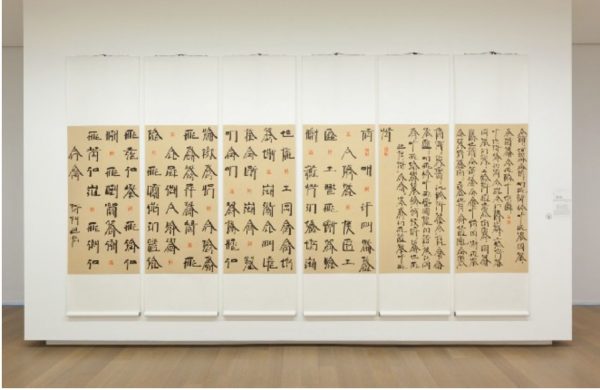

In recent years, the art form has also become an important channel for Western exploration of Eastern culture and its aesthetic values. The unconventional nature of contemporary Chinese ink painting has great significance. In the mid-century years, the genre did indeed incorporate abstract, perspective-based, conceptual and other contemporary elements to proudly fashion its own modernity. The modern movement led by established artists such as Qin Feng, Xu Bing and Tian Xutong had a tremendous impact on the more recent development of Chinese ink painting.

Representative exponents of contemporary ink painting include new-generation mainland Chinese artists Xu Lei, Li Jin and Gu Wenda; creative avant-garde experimental artists such as Xu Bing. These artists are all at the forefront of the trend, developing the different facets and potential of Chinese ink painting.

Contemporary ink painting is not only emerging as a “hot stock” across the auction scene, but it is also leaving its mark in world-class art museums. After five years of preparation, Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China opened at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art late last year. It is the museum’s first large-scale exhibit of Chinese contemporary art, and the event can be seen as a kind of Western endorsement of the art form. In recent years, other venues in Asia and beyond have exhibited ink painting, including the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Princeton University,Harvard University, the British Museum, Musee National des Arts Asiatiques-Guiet, Asia Society New York and China Institute.

Over the past decade, there has been a steady rise in interest for contemporary ink, as evidenced by the increase in exhibitions, galleries and museums worldwide. The common denominator has been both a respect for classical ink paintings and a shared excitement for the emergence of imaginative new ink artists who utilise a new artistic vocabulary.

Indeed, the entire Chinese art scene has embraced the art form. Chinese ink painting marches confidently into the 21st century, drawing on its rich and varied artistic vocabulary and unsurpassed vitality of form – like a recitation of a Chinese poem with deep imaginative power and vibrant reflection.