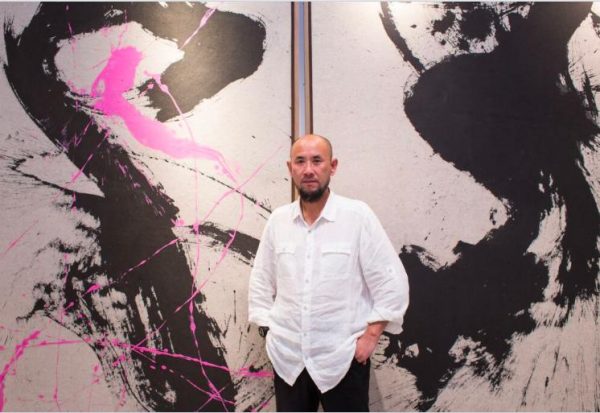

Merging an ink-and-wash and calligraphic style with a western abstract aesthetic, established Chinese contemporary artist Qin Feng re-interprets the age-old medium of ink painting infusing it with a new life and colour.

Qin Feng’s (b. 1961) art blends Eastern and Western qualities. His works follow the traditional Chinese manner of brushing black ink onto paper in a calligraphic style, but Qin’s aggressive physicality and spontaneously applied marks betray a deep understanding of Western gestural abstraction. Qin’s international outlook was born during his childhood herding sheep in China’s harshly beautiful and multicultural, far western Xinjiang Autonomous Region. In his early twenties, Qin travelled east to study at the Shandong University of Art and Design. Then, in his thirties, he taught at the Berlin University of the Arts, before going on to New York City and Boston, where he did a residency at Harvard University.

How would you describe the interaction of Eastern and Western traditions in your artwork? How do they relate to each other?

There are three parts to it. The first part would be the physicality of my upbringing. There are more than 40 ethnicities active in that region [Xinjiang Autonomous Region] and more than 20 languages spoken on a daily basis. That’s number one. Even though it is a part of China and they all speak Chinese, the entire culture, the living environment and culture, the way of life, the mentality itself, is very Eurasian, because you have Mongolians, Kazakhstanis, Russians and so on. So, before I reached the age of 20, I was basically living abroad in that region. We were all clustered together. All those religions, Muslim, Eastern Orthodox, etc.

Second, there was a very stark contrast when I moved to Shandong, which is really Chinese. That is where Confucianism was born, and there were these very traditional and historical Chinese thoughts and philosophies. That had a very huge impact. The craftsmanship and artistic philosophy that all that espouses is what I acquired. It’s not just about calligraphy or ‘Chinese art’; it’s also the mindset behind it all, that education. And at the same time, because of westernisation – in China generally and specifically in that region – that was also when I was introduced to Western culture, and by ‘culture’ I do not just mean in books and lectures you attend; it’s in movies and food and other things.

And then you think about the political circumstances of that day and age when China was on the brink of modernisation. It was a very turbulent decade [the 1980s] and you had the rise of scholar-artist students who were trying to strive for a new China. That way of thought is especially important, because that was a really crucial period of time for the enlightenment in China after it was established in 1949 and after Deng Xiaoping and all that. After that, when I went back to Xinjiang, I had already been exposed to so much and with my new outlooks and horizons I started engaging myself in creative pursuits, not just art, but with stage props and theatre designs, conveying traditional theatrical symbolism with new terms. It wasn’t like I just locked myself in a studio. Then it was Beijing for four or five years and then it was Germany. I noticed there was an overall atmosphere [in Beijing] with students in the academic realm, and so for political reasons in China, I had to go to Germany, which was a lot more tolerant. In Berlin, I taught at the university level but with a translator. I was teaching contemporary art, the creative process and painting, Eastern and Western together. I was part of the faculty and was expected to expound upon my own practices to European students.

Then it was Beijing for four or five years and then it was Germany. I noticed there was an overall atmosphere [in Beijing] with students in the academic realm, and so for political reasons in China, I had to go to Germany, which was a lot more tolerant. In Berlin, I taught at the university level but with a translator. I was teaching contemporary art, the creative process and painting, Eastern and Western together. I was part of the faculty and was expected to expound upon my own practices to European students.

So would you say that multiculturalism is readily identifiable in your individual paintings?

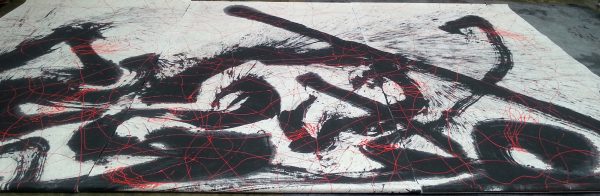

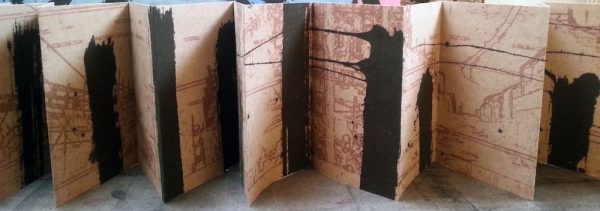

From an academic perspective, definitely. That is something that has been commented on by art critics and people who teach art within the field. If you were to dissect a piece and look at the lower hand corner of this work [pointing to Portraits of the Great No 054 – 2014], for instance, you may say is it Eastern or Western. If you were to take out the ink wash part over here, you might say that is very Chinese because it is very easily recognisable. But you cannot just point a finger at it and say this part is Chinese and this part is Western and this part is obviously influenced by American modernism, because even if this material is wielding in an old Chinese fashion, another material over there is probably not part of the tradition of ink painting.

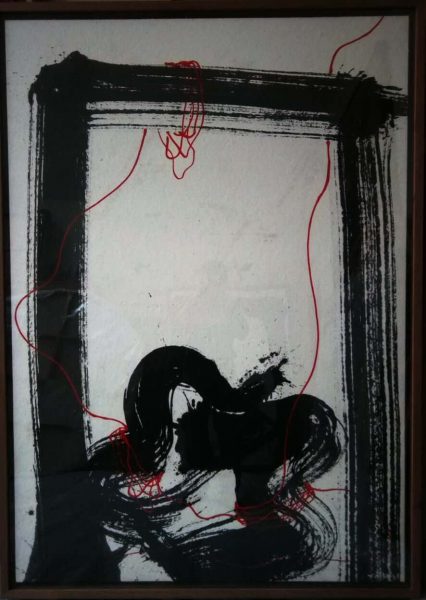

For example, with the red lines especially, that [paint/pigment] is probably more of a Western material but then fused together here with other things, in this work, it doesn’t seem Western anymore. So it is not just about embodying all of these different types of culture anymore, it also about the period or epoch we are in right now, the age of modernism, the age of digitalisation, but then at the same time paying homage to historical practices and where this all developed from – it all had an origin – and having a platform that represents all of that.

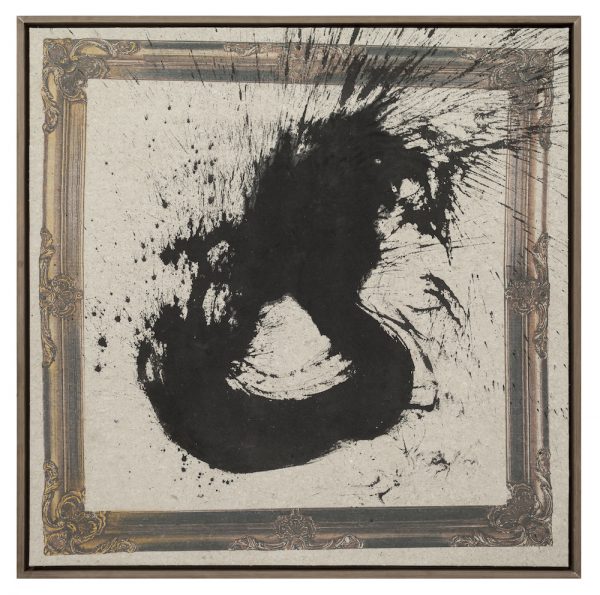

In this work the printed frame evokes Western classicism, but they all seem to coexist somehow. It’s like how the iPhone is so successful, because it doesn’t just present itself as an ‘American invention’, but it’s got more to do with being a technological breakthrough. How people can use it to communicate, sending messages for instance, breaks boundaries. It doesn’t matter who you are. Who is going to say ‘I don’t think we should communicate’. If you can achieve that communication, it means you’ve succeeded.

Tell more us about the paper you use.

In the first place, this paper was conceived because it has to be able to carry and compliment the colour scheme that I had in mind. It was tailor made to fit what I had in mind. And the blotchiness and the pink pigment has to be able to come through in a certain way; that’s why the paper was made in such a way. Because if you use something that is water repellent then how are you going to hold that colour in? It has to be absorbent enough but at the same time it has to not have that washy kind of feeling. That cannot be achieved through traditional Chinese xuanzhi (宣紙) (rice paper).

Canvas has always been associated with the finest Western art, from the Renaissance period onward, as long as it’s not works on paper. But xuanzhi (宣紙) is for traditional Chinese ink painting, whatever dynasty it is doesn’t matter, whether it is a portrait or a landscape. By combining those two qualities of cotton and rice paper and creating this you are jumping out of those parameters and you’re creating something new, while at the same time paying tribute to the origins. Still, the quality of it surpasses the original predecessors. This is a paper of our century. We are doing our own thing now. Multiculturalism is not just about ideas; now it is physical, it’s manifested.

The layers of paper are not just stacked right on top of each other, but you see the layering until you reach the top layer. Well, think about it as a journey through time. We were here before, but as you slowly peel off these layers you will eventually find those roots. It is a journey of development in art history and practices. The red colours themselves are entirely Western; this is not Chinese ink. But as part of the formula for creating this paper, I have infused into it my whole existence and memories.

You see the wooliness? It’s like my bedsheets, all through the years. So part of me is there. And those things symbolise the environment in which you were in. It’s not just me as an artist, but also my own memories and the collective experiences of those communities I was a part of. Cotton, linen and Chinese xuanzhi, those fabrics from my own belongings go into this, the remains of a human experience. But however these things were conveyed or presented it’s all a form of beauty, of art, so at the end of the day this is what you get.

Is there a physical or sexual aspect to the “Desire Scenery” works?

You know how some artists are very specific about what they are conveying? They’ll say ‘I see your point, but that is not what I’m trying to do’. I am not one of them. Obviously, there is a general direction, but then some people think about humanity, some people think about the course of art, some people think about history, and that’s all valid to me.

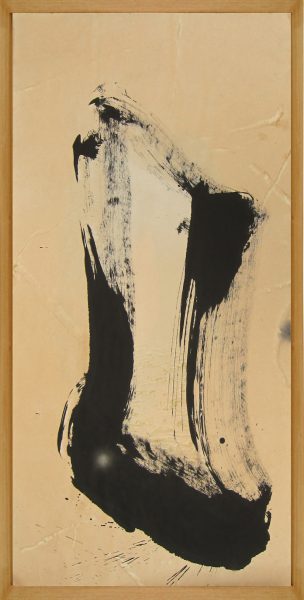

You did not really care how some of your paintings were hung, horizontally or vertically, and that seemed very strange. Would you explain your mindset?

There was a study conducted at MIT that says whenever there are three or more works however they are positioned or oriented they all work together somehow. The series is called “Desire Scenery”. Originally I thought how should I put those two (concepts) together. What are you looking for? What do you see? You see what you want. You want what you see. And then the scenery ends up being what you perceive. There are multiple angles. It’s like a glass of water. If I turn it over and it doesn’t spill you would ask ‘Why is water still in it? It is supposed to spill.’ You are not bound by those laws of physics with this type of [abstract] art. But with a glass of water, even if you spill it, it is not the end of the world. You just have a water puddle.

My art is really aligned with my philosophies, rather than a purely pictorial depiction of real life. If you spin the work 360 degrees, it will just look different at different angles; you might see different things a little. You stare at this one object standing up or sitting down for your whole life and then all of the sudden one day you lie on your side and you think, ‘Oh, I’ve never seen this before.’

There were these people who once came up to me and looked at one of these paintings and said: “Is this new, I really like it.” And I said “That is the same piece you saw before” and I realised I had flipped the orientation. Then every time I would turn it, they would say “Oh, it is so much better than the last time! It is totally different from the last time.” But by the fourth time I had turned it 90 degrees, we went back to square one and they would say “Oh, I’ve seen this before! But I can’t put a finger on it though.”

Where are you living now?

Beijing, Shanghai, New York. I have four studios.

How would you compare the art scenes in Beijing and Shanghai to the art scene in another economic hub of Asia, Hong Kong?

In Hong Kong the pace is so fast. Even the rhythm of crossing the road is totally different. The atmosphere doesn’t allow you to create art. It’s not as apparent as it would be in Beijing or Shanghai for sure. Commercially speaking, yes, it’s not up and coming; it is established already. But from a creative perspective, no. Hong Kong is starting to become like Shenzhen or the other way around. Shenzhen and Hong Kong are beginning to blur into one in terms of the culture and the pace of life. I don’t live in Hong Kong, but these are my impressions. I feel there is a sense of connection with the past, with art history, through the older things. But aside from these icons, I don’t have strong impressions of Hong Kong that would really separate it or make it stand out from, say, Shenzhen.

Because in Beijing you have a lot of dialogue going on. Artists hang out and we have filmmakers and you have all of these exchanges, but in Hong Kong, no. It’s not part of our culture here in Hong Kong to just hang out and just talk about ideas for three or four hours. It’s ‘Time to go to work, see you’ here in Hong Kong. You’re always pressured to think about your next step here. You can’t just take a breather.

What direction do you see yourself going in the future with your work?

My works are part of a twenty-year plan actually. It’s not going to be a departure from my ideas because it is what I believe in, but how I present it and how it matures and develops later on, it will hold up for a while. So it will not be ‘I will dedicate the rest of my life to “Desire Scenery”’. It is all interconnected.

And it will still be here after 35 years. The significance of the red thread is so important that it will always be with me even in my final piece. However, the way it is presented, it may even just be an edge or a halo-like aura. The lines will be with me. And then one day maybe later on people will see that red line and say “Oh, that is a Qin Feng piece; I recognise that.” It might not be depicted by a brush or pencil, but the lines are there.

*extracted from the original article by Art Radar.