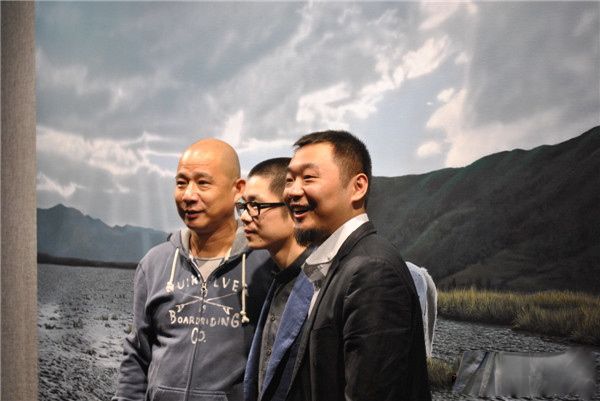

Contemporary art scene’s most recognisable artistic duo Tamen’s name is a common ubiquitous Chinese word. It is the third-person pronoun for “they” used in daily conversations when referring to two or more people other than one’s self. Just like their namesake, there are no distinct physical attributes or cultivated personae that might distinguish Lai Shengyu and Yang Xiaogang as unconventional. If anything, they appear quite ordinary.

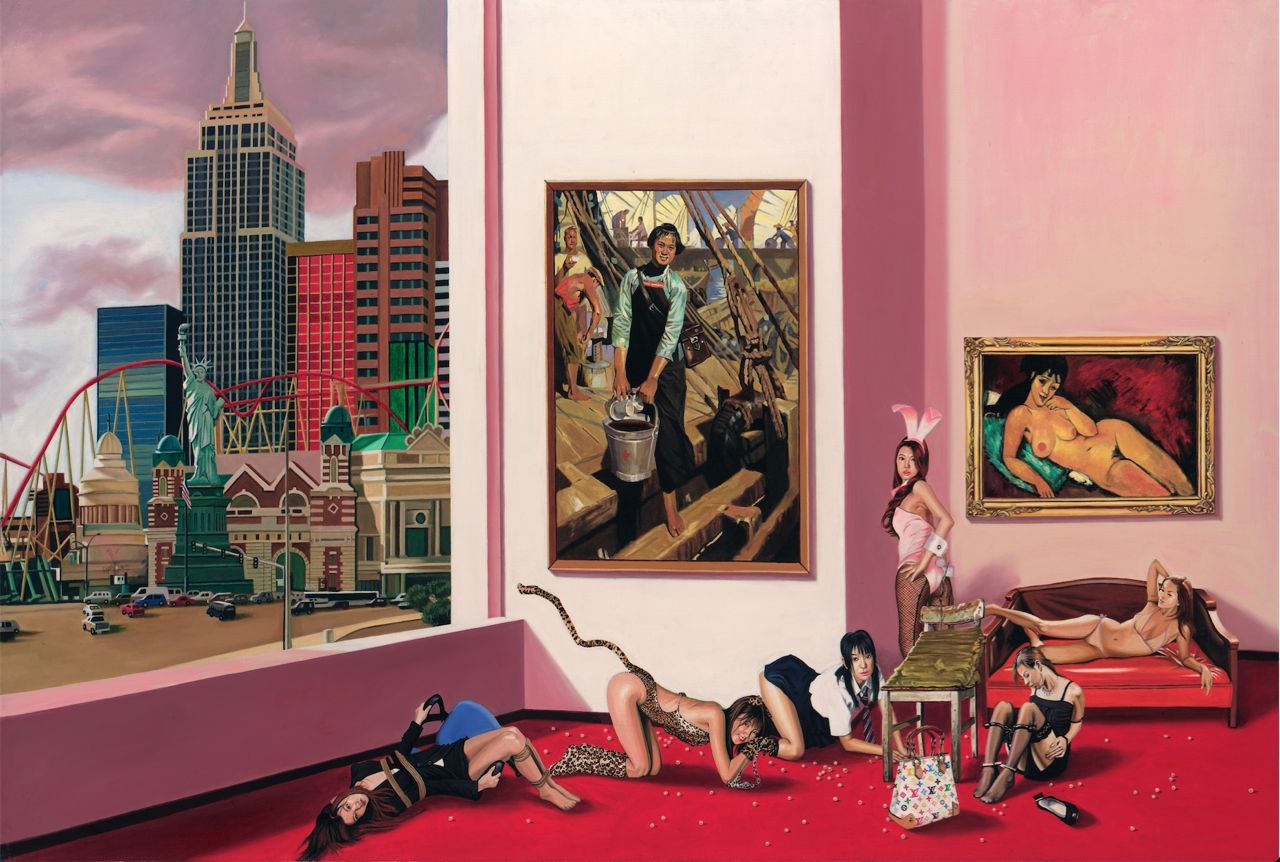

Yet, the vast artistic output collectively produced by this two-men incorporation is far from commonplace. Surreal, flamboyant, wild, incomprehensible, contradictory and spectacular are just a few words that have been used to describe their paintings by critics and viewers alike. YANG GALLERY Team recently sat down with Lai and Yang in their Beijing studio in hopes of eliciting personal insight on the relationship and practice of this unique pair.

Tamen formed in 2003 and consists of Lai Shengyu and Yang Xiaogang. Sharing a canvas and employing a collaborative painting technique, whereby each artist takes his turn to express opinion through figurative imagery, Tamen’s pictorial dialogues are the antithesis to individual “self” expression in artwork.

Born in China’s Hunan Province, artists Lai and Yang moved to Beijing in the 1990s to study at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA), where they received their master’s degrees in the Department of Printmaking. It was during their time at university that Tamen decided to collaborate on paintings as a way to illustrate a less literal conversation about art and life in China. Their method of co-painting has altered very little since their early works—each artist offers an image to be elaborated, contrasted or juxtaposed by the other painter.

Collaborating on paintings is not new to China’s long history of art—calligraphers would add prose or poetry to the landscapes of an ink painting. Heroic panels and murals of the communist panels were often attributed to more than one painter and it was extremely common for a canvas to be shared by two or three painters during the 1980s. At the core of Tamen’s paintings are the relationships that dominate— between the landscape and figures and between a subject and audience. Whether the viewer is inside a room, on a building site, or standing in a field of grass, they are engulfed in the landscape of Tamen. In such a way, the artists replicate relationships in their paintings to reflect a rivalry between individual existence and collective will.

Much of Tamen’s early works such as the Same Room series have evolved from the amalgamation of imagery and integration of movements such as Pop Art, Surrealism, and Social Realism that converged in the Chinese contemporary paintings of Cynical Realism and Political Pop in the 1990s. The urbanization and process of construction and destruction of cityscapes took prominence in their work as a transition from inside the room was moved outside. Over time, Lai and Yang have negotiated their own engagement with tradition and recent history in a more serene narrative. Most recently the question of cultural identity and exploration of “national” aesthetic has emerged as they leave behind the city and urban architecture to re-discover the countryside via Chinese landscape painting.

They are an intriguing collective, not only for their ability to share a canvas without conflict, but the capacity and desire to evolve their practice. As a generation born at the beginning China’s opening up policy, the artists have witnessed firsthand the economic development and urbanization of their cities and country.

1. Your approach to painting and collaboration is quite multi-layered. Can you comment on the process and how you resolve any conflicts or differences as you create a work? How controlled is the dialogue? Are there preliminarily sketches and how much is left to chance as the painting takes form?

Different ways of thinking and values are exactly what we need to produce images that are one-of-a-kind. Therefore, we don’t need to limit the boundaries of our conversation. Among the hundreds of works that we have created, there are a plethora of rich topics that almost cover every aspect of life in a society. During the art-making process, we set up a platform as background, but we never predict any result, and almost always work with improvisation. Sometimes, we even create on top of a finished work. There is never any pre-planned destination in our work.

2. You gained great acclaim in China and abroad for your Same Room series of paintings that embraced that nebulous territory between the real and the imagined world. While these paintings can be interpreted and appreciated for their own conceptual meanings, there is another layer that shares a similarity if not homage to the paintings in the early 1980s such as Zhang Qun and Meng Luding’s A New Era: Revelation of Adam and Eve, which juxtaposed Western art and religious imagery with references to a new and promising future. Overt examples such as broken frames or sun shining through a window in a dark room could be interpreted as artists’ feelings of entrapment and desire to break free from past political and ideological confinements.

Your earlier work shares the above mentioned surreal instincts and numerous references to Western and Chinese icons of both art historical and popular culture. Do you see your generation as a continuation of that represented by the early ‘85-movement consciousness? Can you elaborate on where you situate your work in relation to the “first generation” of Chinese contemporary painters?

It seems that our discussions are more complicated than those. First of all, a “house” serves as a stable platform for our art-making, and we talk about “change and no change” in terms of its philosophical implications. In addition, urban development has been the core of Chinese society in the last 10 years, and the “house” has become a window that connects an individual and his society. The stories that happen in a house reflect the social changes in entire China. Any historic trend/movement must be enriched into the mind of the next generation. Perhaps we would carry on the way of thinking generated by the ‘85 New Wave Movement, but this relies on the observation of our audiences when looking at our work. Our works can’t be more conservative than the first generation of contemporary painters, because we progress with passing of time and the evolution of history in order to produce new values.

3. More recently you have shifted towards exterior scenes in which natural landscapes take prominence in the construction of the image. Your earlier Same Room series included the interdependent spaces of indoor and outdoor and are often read as metaphors of the outer physical world and one’s inner world of experience. Can you elaborate on this shift in perspective from being inside the room to outside and immersed in the landscape?

We have been living in Beijing, a metropolitan city, for a long time. More and more people suffer from the “urban disease” (symptoms of urbanization) due to the high-speed economic development, and we are not exempted from that either, always thinking about escaping the city. Our bodies have yet to leave the city, but our works have reflected these thoughts by moving away from the city. From the urban sceneries in the period of “in the same house” to natural landscape, this is a natural transition, implying the changing of the society and our own experiences.

4. You are well versed in Western art history and its painting language, similarly you did not study ink painting or calligraphy in art school education so how confident do you feel with the more recent inclusion of traditional philosophical approach and theories into your works? The physical changes are oblivious, the canvases are smaller with fewer figures but perhaps the biggest changes are in your techniques, brushstrokes, pigmentation. How much of your work is now about the process of painting or the importance of technique over the subject matter? And how does paying more attention to process of creating a work affect the dialogue?

We have studied ink painting and calligraphy since we were young. This has had a fundamental and deep influence on us, much deeper than what we studied in art school, which enables us to have a better understanding and well-formulated opinions of traditional philosophy and thinking. We try to insert traditional Chinese culture into contemporary works. There are differences between Eastern and Western cultures, but they are not opposite to each other, and we try to make a connection through our “conversation.” There is no way to calculate the percentage of skill versus subject. Making art is about sensibility, which requires talent and feeling. We always adjust our works according to things that have touched us.

5. Many artists engage with Chinese tradition in their work, even if to subvert and challenge it. Chinese art historical culture seems to be guiding your most recent choices of reference, materials, and media. How is the way you negotiate with tradition also relevant to present-day concerns?

Tradition is not just on the surface of our work. We have our own unique understanding of traditions compared to other artists. Tradition is complicated and ever changing, and you can’t avoid your own tradition. Therefore it is naïve to rebel against or overthrow tradition, which has become a tiresome discussion over the years. Our work dynamically reflects the social realities and the changing cultures, which is obvious in our work. It awakens us from the hibernation of traditions. This transition does not originate from Chinese traditions, but encounters it unexpectedly, and we fall in love with the traditions as we go further. It’s almost like completing the cycle of spiritual incarnation and reincarnation.

6. Since the early 1990s international art audiences have concentrated their attention on the ideological and social struggles in China, which helped to attribute to the success of artwork that had aesthetic roots in the Western academic and propaganda imagery, such as Cynical Realism or Political Pop. Can you comment on the expectation for painters to make ideological or social commentary in their artwork today? And how does this expectation affect (if at all) your approach to painting?

We are not concerned with the expectations that the audiences cast on the so- called social artists, so it doesn’t affect our attitudes toward painting. Only real social issues and culture can influence our art, as well as our own experience and knowledge.

7. What are the strength and weakness of your duo during your art creation?

Our strengths are that both of us graduated from the Central Academy of Fine Arts with a very solid artistic foundation. Our understanding of art history & philosophy are very through. Since our establishment, we have achieved substantial academic and market recognition. The weakness is that we have not reached a 30-years milestone in our collaboration. Art groups that can persist for 30 years in the world is rare. But, based on the divorce rate of today’s society, the fact that our duo has stood the test of time till now is better than a lot of marriages. (Laughs) It’s a miracle in itself and we are truly blessed and thankful.