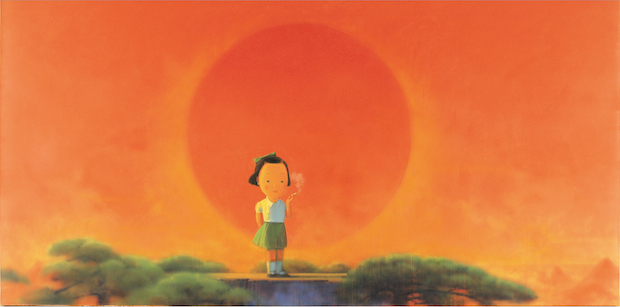

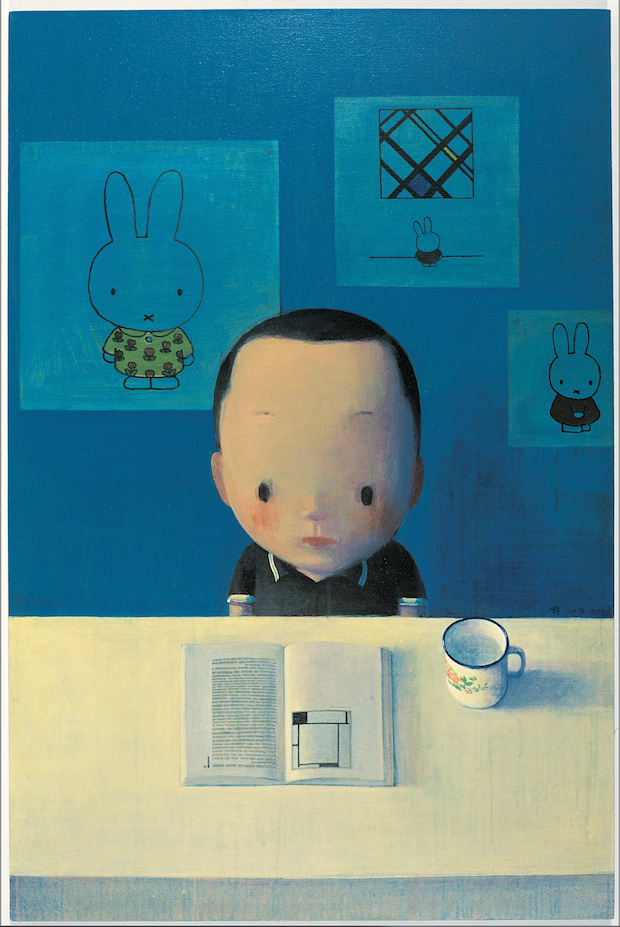

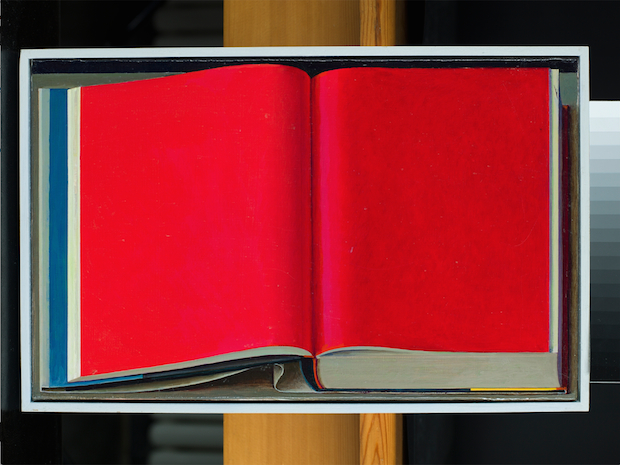

Known for his bright-hued paintings of childlike round-faced figures, acclaimed artist Liu Ye’s new catalogue raisonné includes “a number of works that have never been published,” according to its editor Christoph Noe, who is also the founder of The Ministry of Art and Larry’s List. Published by Hatje Cantz Verlag, the catalogue raisonné features an overview of Liu’s creative output between 1991 and 2015 and encompasses less than 300 paintings created over the span of 25 years.

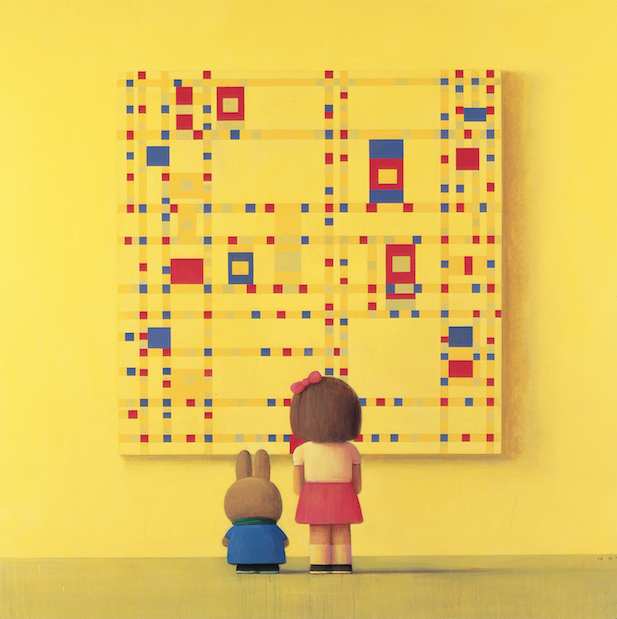

Thanks to his life experience in Berlin and the Netherlands in the 90s, Liu’s works are said to have been influenced by European artists such as Piet Mondrian and René Magritte. Mondrian’s grid-based paintings are frequently seen in Liu’s paintings. The cartoon character Miffy created by the Dutch artist Dick Bruna is another motif that is often seen in Liu’s works. Liu associates himself with the rabbit, which he sees as “smart” and “kind” though it wears no expression—which he contrasts with the Japanese cartoon character Hello Kitty that he has said looks “dumb” to him.

YANG GALLERY team caught up with Liu Ye for an interview to learn more about how his works have evolved throughout the years and his thoughts on the ever-changing Chinese art market.

How do you feel your art has changed throughout the years?

Now I’m more intrigued by ordinary found objects that surround us on a daily basis. In my earlier days, my art was more about imaginary. At that time, I was influenced by Italian Metaphysical Art and Surrealism; René Magritte is one of my favorite artists. Now, I’m paying more and more attention to ordinary found objects around me, such as a book, a few wooden blocks, or bamboo, etc. This has been the main change. The change, of course, wasn’t planned so clearly; it’s arbitrary. I’m not the type of artist who has planned out everything for myself. I like to go with the flow on some level and not be so rigid. It just so happens that I’m more interested in common objects now. The main medium is still painting. As you look into it further, you’ll realize that painting is full of possibilities.

Where do you find inspiration?

In my earlier days, it came from my imagination, childhood memories, and the societal background. Recently, I’ve been more inspired by found objects around me. I think this is almost like a state of meditation. It’s when an ordinary thing can touch you or influence you out of nowhere. I’m relying less and less on imagination, but rather on objects that have no significance or seemingly have no significance.

Do you paint for a global audience or for a Chinese one?

I hope that my works can be for everyone, not limited to the Chinese audience. I think the advantage of painting is that it’s a universal language. There’s no need to set limitations on it.

Your works are said to have been influenced a lot by European art. Do you think the Western audience can understand your art better?

I think the reality is that only a part of the audience in China and the Western countries can truly understand my paintings. It’s not necessarily true that all Western audiences can understand better. In fact, there are not that many people in the West that truly understand art. It’s the same in China, except the percentage (for Western people who know about art) is a little higher. Therefore, I think the portion of people who can truly understand my work is very small, while the common language between this small Chinese and Western audience is outweighed by their ethnic gap.

To put it simply, when it comes to something you’re interested in, sometimes you can have more in common with a Westerner than with a Chinese person. Those in the Chinese audience that can understand my works better are those who have some experience abroad, and are interested in contemporary art. They should have some background knowledge, be well-educated, and share things in common.

Do you think your works are more popular among Chinese collectors or Western collectors?

There are twice as many Western collectors than Chinese collectors (collecting my works). In the 90s when we grew up, there were no Chinese collectors collecting modern or contemporary art. Thus, at the time, almost all of my works was bought by Western collectors. In the decade after 2000, more Chinese collectors emerged and they are very active. They’ve already caught up (with the Western collectors). Many of my paintings once in the hands of Western collectors have changed hands to Chinese collectors via auctions or secondhand sales. Now, the proportion of Chinese collectors is catching up to that of Western collectors.

In recent years, Chinese collectors are becoming more and more active in the auction market; works are purchased by Chinese collectors at increasingly high record prices. Do you expect this trend to continue?

I think it will continue in the long-term. In the short-term it might fluctuate, but overall this trend will continue to grow as long as nothing catastrophic happens to China’s economy or society. Through 20 years of observation, I think the most important trend isn’t the record-breaking sales, but that ordinary people in the middle class are starting to collect as well. They show up in galleries and auction houses and have started to buy some not-so-expensive works from young and emerging artists. It’s become part of their life. This serves as a good beginning and foundation. The collecting trend is growing in China; this never happened before. I think this trend is crucial for collecting Chinese art.

Do you have your own collection?

Yes, I have my own collection. Even in the 90s when selling a piece wasn’t so easy and up until today, I always pay attention to young artists and collect their works; it has became part of my life. I only buy contemporary art and not antiquities because I’m more interested in young and emerging artists. First of all, I must like the work myself; secondly, I buy art to support some younger artists; lastly, I prefer modern and contemporary art. I have a sense of achievement while I collect; some of the works’ market value has risen.

Collecting to me is just for fun. I do it because it reminds me of my similar situation when I was younger like them, so I find it interesting.

As you have not had assistants to work with you in recent years, do you feel the pressure from the art market to produce more works in a year?

I’ve only had an assistant when editing this new catalogue raisonné, but I don’t have one when I paint. Thus, I feel like I’m not an artist of this era. My way of work isn’t fit for it. Because I work alone, I have to deal with many trivial things as well. However, I think this is important because art is a spiritual product. Its spiritual component weighs a lot and this component comes from people. The intimate relationship between the artist and the artwork is crucial. I think industrialization has created enough problems already. Changing an artistic product into an industrial product should not become a trend; perhaps an experiment, but not a future trend. It would be harmful to art.

I usually produce eight or nine pieces of work per year; four if less, over 10 pieces if more. My way of working goes with the flow and is largely impacted by my moods and experiences of failure. Therefore, under the contemporary art system, not being able to produce a standard number of paintings in time may cause some problems in collaborations. For instance, the galleries that represent me think I’m a little slow.

If you would like to have a museum show, which museum would it be?

As an artist, perhaps theres never a point where I can easily choose where to have my exhibitions, so it doesn’t matter what I say or where I choose. I’m at a position for people to come to me, but I have rejected at least three museums because their space didn’t quite suit my paintings. I’m not in a rush to hold exhibitions, but if I do, the museum must fit my works in terms of space and temperament.