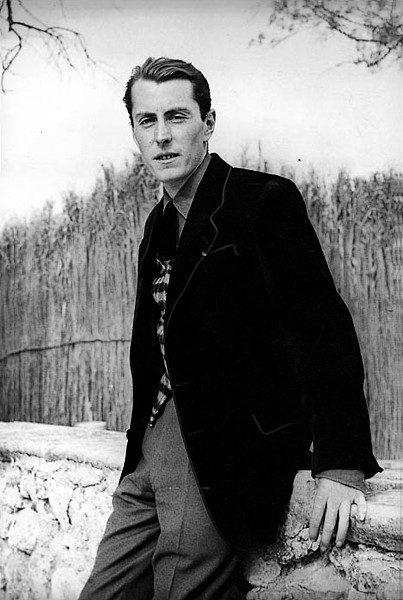

On a sunny afternoon in the 1950s, Pablo Picasso was sitting with his children on the terrace of a café in the south of France. Another artist arrived. “Look, there is Bernard Buffet,” said Picasso’s children. They jumped up and asked for the autograph of the young, handsome, awkward man who was – joint equally with their father – the most celebrated painter of the post-war world, a modern master who had made a colossal fortune from his work by the age of 30.

After a meteoric rise to stardom, Buffet fell victim in the 1960s to a campaign of denigration in his home country, led, among others, by Picasso. The Spanish genius detested Buffet for rivalling his fame and certainly never forgave him for becoming a cult hero to his children.

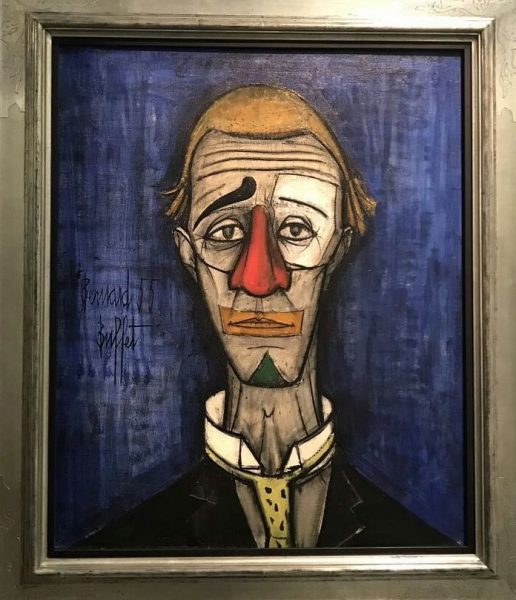

Picasso’s mythical status, and commercial success, continues to grow long after his death. Buffet remained successful for half a century; up to a point. He was for many years a great favourite with non-academic lovers of art, otherwise known as “ordinary people”. In the 1970s, no middle-class sitting-room in Britain was complete unless it had a stiff-backed orange couch, a television on splayed legs and a print of a spiky clown’s face painted by Buffet.

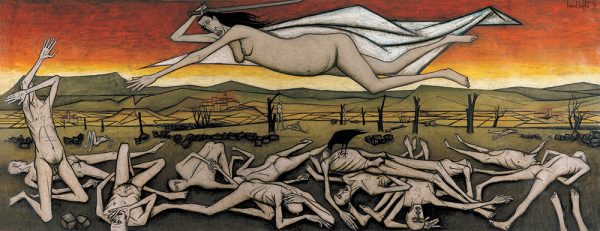

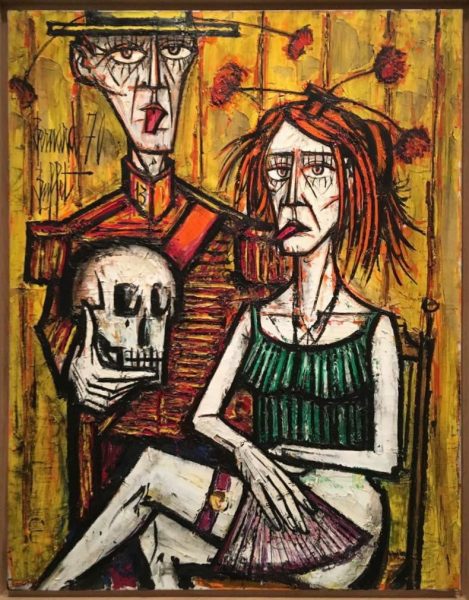

He has also been consistently admired by art critics in other countries, especially Japan and the US. In France, Buffet’s reputation as a serious artist imploded in the late 1950s. Up to, and after, his suicide 10 years ago, he was treated by the French cultural elite as an object of mockery and contempt. His voluminous work – sometimes harsh, sometimes sentimental, using garish colours and bold lines reminiscent of comic books and cartoons – was “not true art”. Buffet, it was whispered, was a purveyor of kitsch, a mere faiseur (poser).

But he remained commercially successful and wealthy, and killed himself only because he had Parkinson’s disease and could no longer paint. Was Buffet a genius or a charlatan? The debate, closed decades ago in his favour in the rest of the world, may finally be about to reopen in his home country.

According to official French taste – and there is still such a thing as official taste in France – Buffet remains an artistic outcast; art school courses refuse all mention of him. But, even in Paris, there are signs that the half-century of mockery may finally be coming to an end. The national museum of modern art, on the upper floors of the Georges Pompidou centre, has a large collection of Buffet paintings. For decades, the museum had kept them locked away but, three months ago, five Buffet canvasses were finally hung on the Pompidou centre’s walls, alongside masters such as Matisse, Braque and Leger.

“The wind is finally changing,” said Henry Périer, art critic and historian and curator. “A younger generation of French art critics and art lovers has looked at Bernard Buffet without the old prejudices and snobberies and has been startled at what it has found. Most people in the French cultural establishment have dismissed Buffet from the 1960s onwards without looking at his work, certainly not his later work.”

Opinions may, reasonably, differ on Buffet. He may not be to be everyone’s taste. What is extraordinary, something with no parallel in the history of modern French art, is that a painter should have been once so admired, and remain admired abroad, but fall so utterly from critical grace in his homeland.

In 1955, he was chosen by 100 critics as the most impressive young painter in the world. In 1956, he was given a spread in Paris Match in which he was presented as the “young millionaire painter”.

Maurice Garnier is a gallery owner and a friend of Buffet until the artist died in 1999. M. Garnier believes it was Buffet’s lightning success and riches, just after the Second World War, which helped to turn the art establishment against him.

“He sold too well,” M. Garnier said. “He made a lot of money. He lived in an ostentatious way. The powers that be hated him for all that.” Buffet incurred, above all, the enmity of two of the great cultural figures of post-war France. The first was Picasso; the second was André Malraux, the writer who became President Charles de Gaulle’s minister for culture in 1959. Picasso would enter Paris galleries and stare at Buffet canvasses for hours, sometimes glaring in silent hatred, sometimes telling visitors how much he hated what he saw before him. Malraux also detested Buffet. M. Perier believes Picasso influenced Malraux, who knew little about art, but he says the culture minister’s motives for bad-mouthing Buffet were also partly political or art-political.

“Malraux was determined to re-establish the reputation of Paris as the art centre of the world,” M. Périer said. “He decided that the ‘abstract’ movement of the 1950s was the vehicle which would achieve that aim. Buffet was anything but an abstract painter. His success and his reputation threatened to muddle the argument that the future of art was abstract.”

Buffet also made another powerful enemy, or at least alienated someone who might have protected, and boosted, his career and reputation. In the 1950s, Buffet, then a homosexual, was the lover of Pierre Bergé, the man who later became the lover and business partner of the fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent. In 1958, Buffet had a spat with Bergé over his new friendship with the then debutant Yves Saint Laurent. Buffet took up instead with a young woman. Perier believes Berge would have reconciled the art establishment with Buffet if the young lovers had not fallen out. M. Garnier goes further and says Buffet attracted the enmity of several powerful gay figures in the art world because he switched his sexual orientation.

Sexual politics and artistic politics apart, is Buffet’s art any good? Does he deserve once again to be compared with Picasso?

M. Perier is cautious. “There is no doubt in my mind that Buffet is a great artist. Should he be placed on the same level as Picasso, as people did in the 1950s? It may be debatable for some, but Picasso has benefited from a Buffet effect in reverse. Sometimes, I stand in front of a Picasso and I really cannot decide whether this is truly a good painting or whether I’ve just been conditioned to believe it is a good painting. “With Buffet, now, at last, younger generations are beginning to really judge for themselves.”