During her lifetime, Frida Khalo had only one solo show in New York City, at Julien Levy Gallery in 1938. Now, more than 80 years later, the great Mexican artist will take her rightful place with what is sure to be one of the city’s biggest blockbusters of the year, the exhibition “Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving” opening today at the Brooklyn Museum.

The show is an expanded version of “ Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up”, a showcase of her never-before-seen personal garments and effects that ran through November at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. It’s the biggest Kahlo show in the US in a decade—and that includes the Dallas show that made it into the. Guinness Book of World Records for staging the largest-ever gathering of people in costume as the artist.

“A show like this provides an opportunity to dig deep and get a fuller picture of someone you think you know well,” exhibition co-curator Lisa Small told artnet News during the show’s press preview. “It’s tackling an artist who is an icon.”

The Victoria & Albert show that unveiled these objects to the public was a monster hit, staying open two extra weeks and for 48 hours straight over its last two days. It was also something of a revelation, providing greater context into Kahlo’s deeply personal self-portraiture and carefully crafted image. The new exhibition is the first time these items have gone on view in the US.

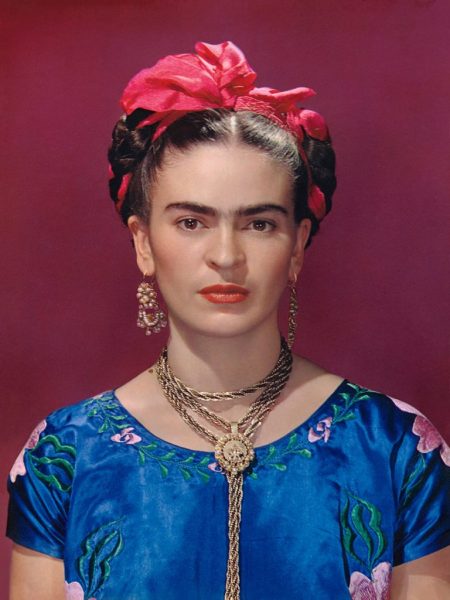

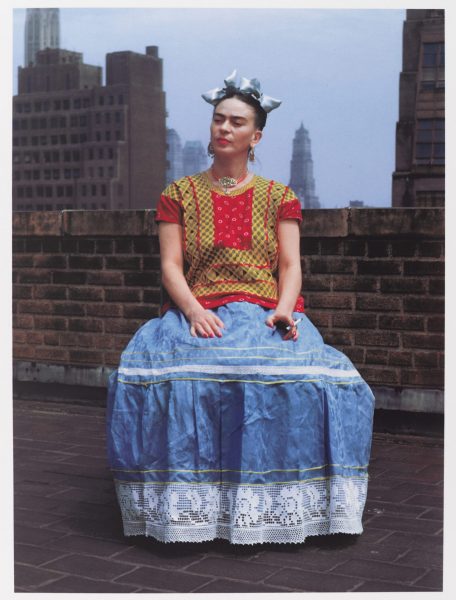

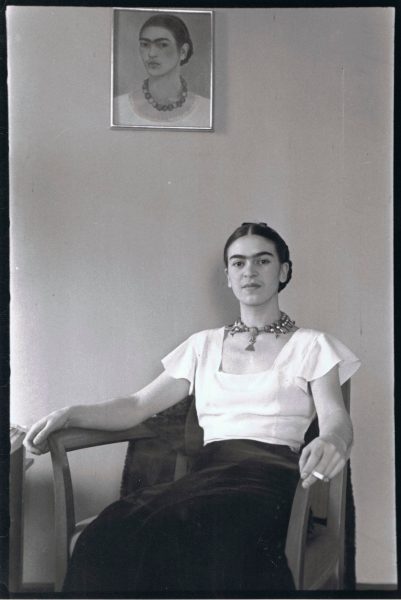

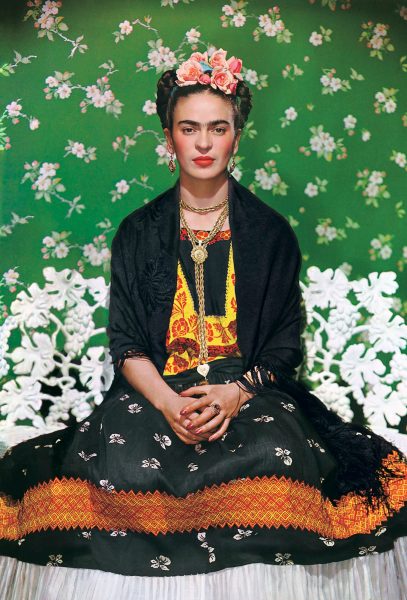

The New York show has been augmented with Mesoamerican ceramics from the Brooklyn Museum collection, similar to the artifacts that Kahlo and Rivera used to decorate Casa Azul. The exhibition also adds some 40 archival photographs of Kahlo. The daughter of a portrait photographer, Guillermo Kahlo, Frida went on to develop close friendships with many great photographers.

“There was this magnetic quality that she had”. “Kahlo is among the most photographed artists of the 20th century.”

Visitors can enjoy her colorful rebozo shawls, but they’ll also come away with a greater understanding of Kahlo both as an artist and a person, from her tumultuous marriage to Rivera to her love-hate relationship with New York City. They may also marvel at the patronizing ways Kahlo, now significantly more famous than her husband, was treated. One wall label in the show reproduces a newspaper article about Kahlo with the headline: “Wife of the Master Mural Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art.”

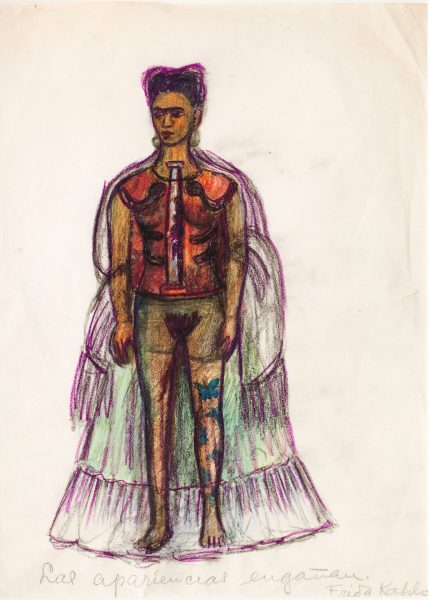

A number of garments on view show how Kahlo adopted the indigenous Tehuana dress as a way to embrace of her Mexican identity. But the voluminous garment also masked her disability; Kahlo was in a devastating bus accident as a teenager, breaking her spinal column and derailing a planned medical career.

Kahlo was periodically bed-ridden after the accident. As a treatment, doctors would wrap her torso in plaster corsets, which Kahlo would paint. Several of these corsets are included in the exhibition, along with the prosthetic leg Kahlo relied on for the last months of her life, after her own was amputated.

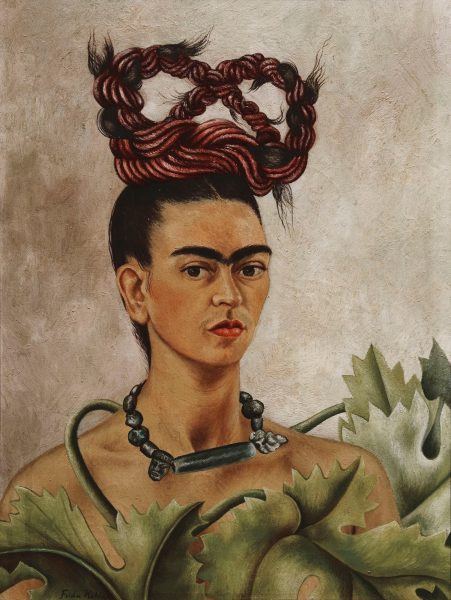

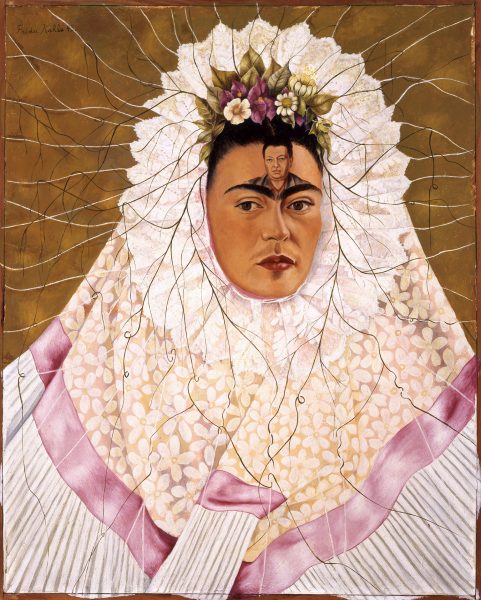

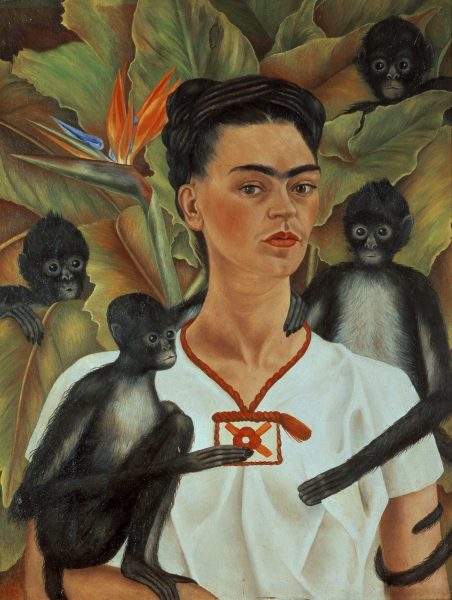

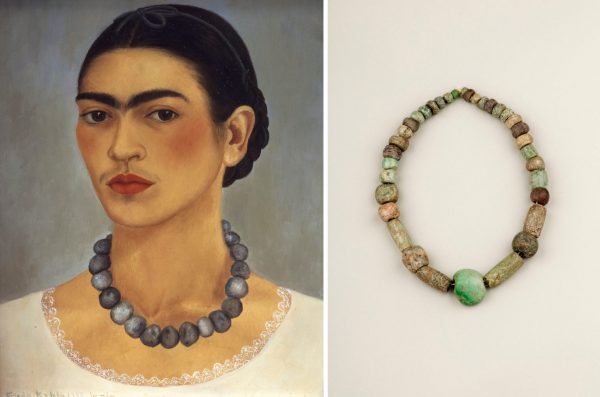

Despite concealing her condition in her dresses at times, Kahlo also shared her pain with the world. The show includes a photograph in which she proudly reveals one of her plaster corsets, as well as a self-portrait in which she’s posed in an elaborate leather orthopedic brace, which is on view in a nearby case. Seeing in real life the very objects that appear in portraits of Kahlo is undoubtedly the highlight of the show.

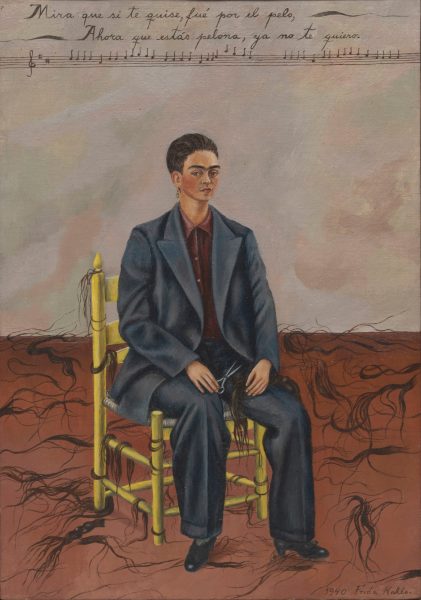

Nevertheless, the display of these objects has generated controversy. Although Kahlo’s significance as an artist is unassailable, her 21st-century fame is due perhaps in equal measure to her fashion—from her traditional Mexican garb, to her unibrow, to her unconventional embrace of men’s clothing. But does focusing on a woman’s clothes detract from her career as an artist? Would a male artist ever see his clothes and toiletries displayed in a museum retrospective of his work?

“It’s a very legitimate question,” said co-curator Catherine Morris, who works in the museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. But she maintains that Kahlo’s self-portraiture benefits from the juxtaposition with her things. “When you have examples of clothing, jewelry, items related to the lived experience of disability that the artist herself painted on, that are included in Kahlo’s paintings and in the photographs that other people took of her, it seems to me it’s a conversation that has to include this kind of source material.”

This approach certainly wouldn’t work for every artist. “I’m not going to do an exhibition of Helen Frankenthaler with her clothes,” said Morris. “But women are often so heavily burdened by their identify in relationship to the way they look and the way they dress. Why not have an exhibition that acknowledges that?”

*extracted from artnet.com