In a corner of Tan Swie Hian’s studio in Telok Kurau is a futon, a once-plump round cushion slightly flattened from the daily weight of his long meditative sessions.

The first thing the Buddhist does when he wakes every day is recite sutras as well as prayers and meditate. The 74-year-old can spend hours in samadhi, a state of consciousness so deep it lies “beyond waking, dreaming or deep sleep”.

Meditating, he says, trains the mind to be unfettered – not possessed – and intuitively clear. “The prerequisite for creation is the freeing of the mind… A free mind sees beauty in all that exists.”

His quest for a free mind permeates his works and is perhaps responsible for making him one of Singapore’s most fascinating, versatile and lauded artists – and the most expensive.

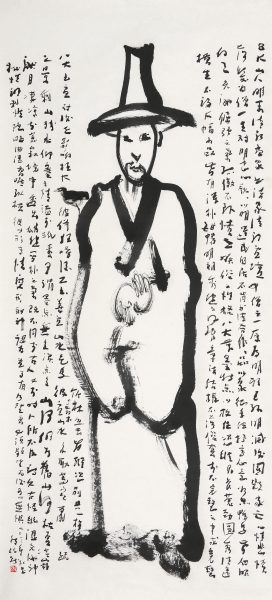

Three years ago, his portrait of Bada Shanren, executed in just 60 seconds, fetched $4.4 million at an auction in Beijing. A vision of the 17th-century Ming prince turned hermetic artist had come to him while he was meditating. Another meditative vision that he rendered with oils and acrylics on canvas, When The Moon Is Orbed, fetched $3.7 million two years earlier.

Chronicling Tan’s achievements can be a giddy exercise; they are hard for many artists to trump. Entirely self-taught, he is also masterful in sculpture, print-making and seal engraving, besides painting and calligraphy.

In 1987, when he was 44, he became the youngest to be elected a correspondent-member to the world’s oldest and most prestigious artistic institution, the Academy of Fine Arts of the Institute of France. In 1996, he was one of 135 international artists to have their works etched on the cliffs of the Three Gorges along the Yangtze River.

Four years later, his essay and calligraphy celebrating the birthday of the Yellow Emperor were carved on a boulder and erected in China’s most important ancient tomb, the Imperial Mausoleum in Shaanxi.

Of awards and accolades, he has many, including the Gold Medal in the Salon des Artistes Francais, Paris (1985), the Singapore Cultural Medallion (1987), the Crystal Award from the World Economic Forum (2003) and the Officer in the National Order of the Legion of Honour medal (2006). The last award is France’s highest honour for individuals who have contributed significantly to civilian or military life.

Time magazine called him “Singapore’s Renaissance Man” in 2003. The description is apt, considering that he is also an award-winning poet and writer, with nearly 60 published volumes to his name. The linguist – he’s fluent in Chinese, English, French and Malay – holds his own on topics from Beat poetry to the Rolling Stones to the life of legendary Japanese swordsman and samurai Musashi Miyamoto. Experts say that his art is arresting because of its layers and nuances – the blend of modernity and tradition, the links between East and West. The artist’s personality is no less fascinating.

He dresses simply, in shorts, short-sleeved shirts and sandals, but gets about in a Mercedes SLK.

He has pledged $10 million to set up a global artist award but lives in an old house, which has no air-conditioning, in the red-light district of Geylang.

He quotes Dante but has an equally consummate mastery of tangy Hokkien epithets.

He meditates for peace but doesn’t back away from a good fight.

He displays modesty, swagger and humility in equal measure.

The fourth of five children, he was born on Pulau Halang, a tiny island near northern Sumatra. His parents, originally from China’s Fujian province, were illiterate.

His father, Mr Tan Chan Pok, started out as a fisherman but through street smarts and business acumen became the richest man in the city of Bagansriapiapi, where the family moved to after 1945. The empire that he built included a fleet of barges and steamers, salt and rice companies and real estate.

“He was head of the Chinese community in the town, and even had his own police force,” says the artist, adding that his father was a pistol-toting giant of a man with shoulders that filled a door frame. Inspiring respect as well as fear, the elder Mr Tan famously rallied his defence force to decimate a band of pirates from Malaysia. The artist reckons that he inherited his temper and his sense of righteousness from his father and his artistic bent from his mother.

“She was a very wise woman and could draw beautiful insects and butterflies and design wonderful floral motifs for embroidery.”

Tan spent a few years in primary school in Indonesia before being sent to Malacca, and later to Singapore, where he studied at Hua Min Primary School in Jurong. He completed his secondary education at the Chinese High School.

Despite keeping company with ruffians in Chinatown, where he lived, he did well in school, especially in Chinese and art. The only exception was in 1960, when he was 17. He skipped classes, got into brawls, flunked all subjects except sports, and was nearly expelled.

“I was going through a lot of emotional turmoil with the underworld,” he says, declining to elaborate. He capped off a bad year by attempting to cheat in his history exam. The invigilator, Chen Wen Hsi – one of Singapore’s pioneer artists – found his notes scribbled on small pieces of paper. “I was caught even before I started. I asked him, ‘Can you tolong?’ He said, ‘Cannot’ – so I walked out,” he says, using the Malay word for “help”.

Made to repeat Secondary 4, Tan was banished to the worst class.

His life, he says, could have turned out differently if not for his English and Chinese teachers, who refused to give up on him, and set him right instead. He developed a passion for literature, poetry and art, even winning several competitions in these fields before graduating from Chinese High in 1963.

At Nanyang University (Nantah), where he studied literature, he became a chain-smoking, prolific writer of short stories and poetry. Gripped by feverish passion, he read and wrote deep into the night, even translating the works of famous writers such as D.H. Lawrence and T. S. Eliot into Chinese.

In 1968, Tan graduated with a degree in modern languages and literature. That same year, he published The Giant, a landmark collection of Chinese modernist poetry. By then, his father had taken a back seat in his business to concentrate on philanthropy and community work. He wanted Tan to take over.

“I told him I didn’t want to be a businessman. ‘What do you want?’ he asked me. ‘I want to write poetry,’ I told him.”

Tan continues: “I broke his heart. He was so angry, he wanted to slap me. I ran away.”

Years later, however, a soft smile would hover over the elder Mr Tan’s lips whenever he saw his son featured in newspapers or on television. After graduation, the artist landed a job as press attache for the French Embassy, even though he spoke no French and did not know how to type. He left the job – which changed his life in many ways – only after 24 years, to become a full-time artist at 50.

At the embassy, he made friends with his colleagues, many of whom were young people his age.

“They taught me French, I gave them Mandarin lessons. It was the 1960s, we talked about the Beat poets and Aldous Huxley,” Tan says, referring to icons of counterculture in the 1960s. His French became so good that he went on to translate the works of French poets Henri Michaux and Jacques Prevert.

Sleeping only four hours a day, he channelled his energy into writing. He also started drawing when he became editor of literary magazine Jiao Feng because resources were limited and photos of writers and philosophers such as E.M. Forster and Bertrand Russell were hard to come by.

Egged on by his colleagues, Tan held his first exhibition at the National Library in 1973. All 32 works were snapped up by the French community, at prices ranging from $500 to $1,000.

That year, he also had a spiritual awakening and got into meditation in a big way.

“For four years, I just concentrated on meditation and didn’t do anything,” he says.

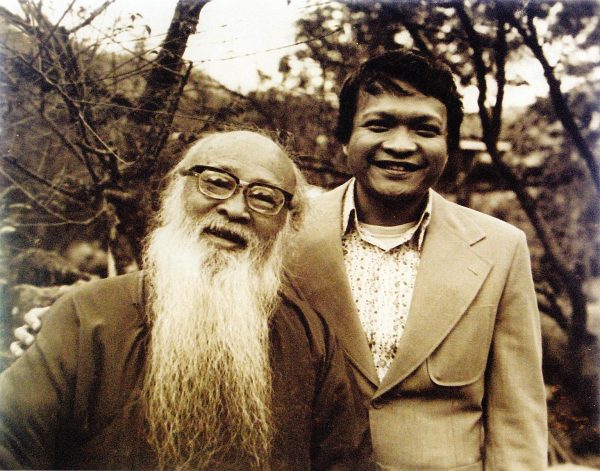

He often ended up at the black-and-white bungalow of his colleague, cultural attache Michel Deverge, to chant and meditate. “One day, Michel told me, ‘Swie Hian, if you continue like this, you will soon be walking on your head.’ And I told him, ‘But that’s what I want.'” But Mr Deverge would have none of it, even threatening to sever their friendship if Tan did not start painting again.

So the artist did, and the results were so impressive that Mr Deverge arranged for them to be exhibited at the Gauguin Museum in Tahiti in 1978.

There was no looking back.

Tan says of Mr Deverge, one of his closest friends: “He turned me into a complete person. Because of him, I could handle all sorts of situations, deal with all sorts of people. He made me a dragonfly.”

By that, he is referring to the tale of the water beetle that sprouted wings, became a dragonfly and discovered a whole new world of light after climbing a reed and breaking the water’s surface.

Freeing his mind, he says, has helped him to discover new mediums.”I’m flying free in the universe of creations,” says Tan, whose works are not represented by any galleries and who has a reputation for choosing his collectors.

His forceful personality doesn’t always agree with other artists. “Many local artists cannot tahan me,” he says, using the Malay word for “tolerate”. “If you live next to Picasso, can you tahan or not?” Turning serious, he continues: “The question is, Do they have my commitment? I walked 1,000 steps every day.”

He did indeed.

For years before the old National Stadium was torn down in 2007, he would walk the steps leading up to the stadium daily, stopping only when he had done 1,000. “Talent apart, it is my determination,” he says, adding that even his family takes second place. His wife, Xiao Fei, is a Nantah history graduate whom he married when he was 27; the couple have two children, a traditional Chinese medicine researcher and a management consultant, both in their 40s.

Last November, the National Library mounted the biggest exhibition of Tan’s works. Titled Anatomy Of A Free Mind, it features more than 100 artistic and literary pieces, including never before seen private notebooks which contain, in exquisite handwriting, Tan’s ruminations as well as drawings of his inner and outer realities.

“Through the works, you can see or get glimpses of how my mind works,” he says of the exhibition, which ends on April 24.

Singapore’s most lauded artist says that there is another reason he loves meditation: “It’s learning about death.”

More than anything else, he wants to have a good death, like that described by Huxley in his novel Island – peaceful, meaningful and characterised by compassion and humanity. He hopes the freeing of his mind will eventually lead to voidness, which Buddhists believe is the nature of all things.

“I want to be out of Samsara,” he says, referring to the endless cycle of birth, death and rebirth. “When you aim high, even if you don’t reach the moon, you will fall among stars.

*original article from the straitstimes.com