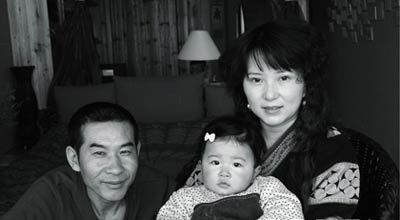

Pan Dehai is one in the trio of artists known as “Three Swordsman”, three of the most influential Chinese Contemporary Artists highly sought after in the world. The other two in this group are Zhang Xiaogang who created the globally renowned “Bloodline Series” and Mao Xuhui, who are achieving over HK$20 million continuously a piece at auction. They were best friends growing up and have had a big influence in the Chinese Contemporary movement.

Like all Chinese contemporary artists, Pan Dehai (born in Si ping City, Jilin province, China in 1956) had to contend, as a youth and student, with the political and ideological hegemony of a still closed communist regime. His first references, as an artist, were historical narratives and literary portrayals after the manner of Soviet social realism.

By the 1970s, however, the country started opening up, and when the young Pan Dehai entered the Fine Arts Department of Northeast Normal University in 1978, it was already commonplace among artists to discuss not only modern Western art, but also non-Marxist Western philosophy, such as that of Kant, Sartre, Schopenhauer and most importantly for Pan Dehai, Bergson.

Western influence was pervasive, although political filtering gave it a peculiar form. Yet the circumstances were still perceived as stifling, and many artists, including Pan Dehai, started looking for alternative places of inspiration. For some, this place was Tibet or the far West. For Pan Dehai, it was Yunnan, where he was first drawn through the sketches of Yuan Yunsheng, and where he soon settled as an art teacher after graduating from university in 1982. “I only knew that Yunnan was an area of ethnic minorities with beautiful sceneries,” he says, “but it was better than I had imagined… Kunming was a quiet city. Old streets, old houses, local special snacks, ethnic minority people’s lifestyles—everything was beauty and novelty to me.”

Pan Dehai soon found special scenery to suit his taste—the Yanmou clay forest. “One after the other,” says his friend, Mao Xuhui, “he painted the red clay forest, the grey clay forest, the pale clay forest— until in the end there was no clay forest anymore, only turmoil and fantasy.” Influenced by the structure of calligraphy and symbols, Pan Dehai found his way to abstraction, by paying attention to the geometric relations of natural objects. His paintings of the clay forest are dated 1982-1983. As he became increasingly abstract, Pan Dehai articulated his process as like being in a daydream, using art as a way to reproduce the “dim illusion of life in the memory.” And he saw his abstract works as a means to depict “spiritual inspiration and revelation” (1983). “When I see a boat on the river,” he says, “I am not content with just the part above the river. I always want to know the other part of it, the part below the water. To me, the real beginning in art is when the vision is broken and the surface world is ended.”

Pan Dehai’s first break came in 1985. By then, China was starting to open up. Western ideas started gaining official acceptance. And young artists such as Pan Dehai and his friends could now exhibit, if not in official exhibitions, then in newly set up galleries and other venues.

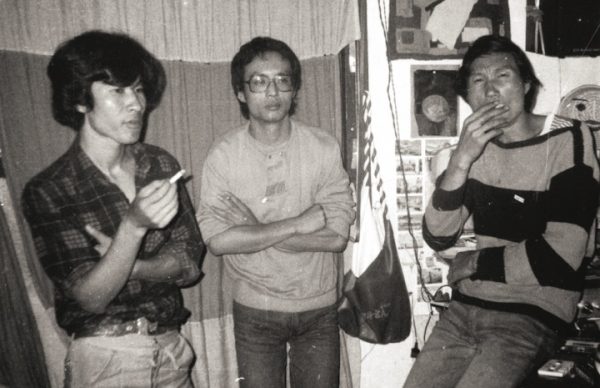

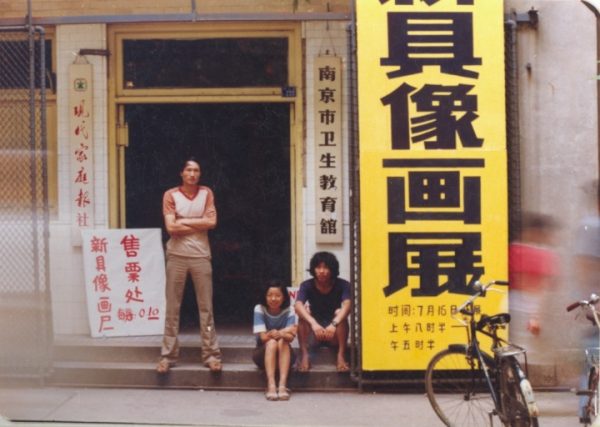

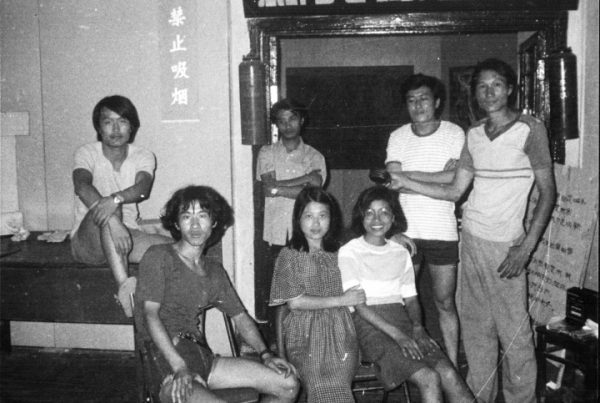

In 1985, one of Pan Dehai’s friends, Zhang Long, came back to Kunming from Shanghai full of enthusiasm. Shanghai was the place to be and to hold an exhibition. But the works on show there were “too sweet, too weak.” Now was the time for talented artists from faraway provinces to try to make it in the great cosmopolitan city. Pan Dehai had 600 yuan, while his friends, Mao Xuhui and Zhang Xiaogang, borrowed 300 and 200 yuan respectively. Zhang Long and two women artists, Hou Wenyi and Xu Kan, joined their group. Before long, they were exhibiting, in a show Mao Xuhui had dubbed: New Figurative Image Paintings.

By 1985, the market economy then blooming in China was transforming the conditions of art production. Impressionism, expressionism, abstraction, surrealism and dada were in full swing. Yet, what was the relevance of imitating past Western art, when the latter was already entering its post-modern stage? Weren’t the peculiarities of Chinese society and cultural background bound to generate a different kind of art? This was unavoidable. Some theorists, aware of the challenge, started discussing the issue of “language purity”, such as it appeared in the works of Xu Bing and Lu Shengzhong. Xu’s “illegible writing” was deemed a typical example of language purity.

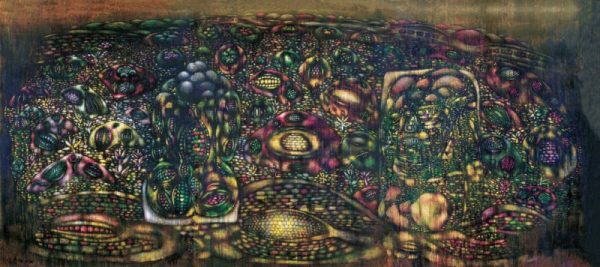

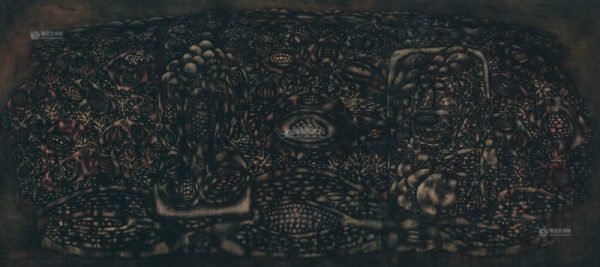

It is against this background of generalized artistic questioning that Pan Dehai came up in 1987 with a new series of works that would ultimately take him back to figuration. His evolution was at first mainly technical: he returned to the use of watercolor, which he had long ago given up for oil. By rubbing watercolor repeatedly, he created what he called “emotional knots”. At first, he wanted to imitate the brick walls of the ancient city of Xi’an. But the result was unexpected: “Once, as I wanted to wash away the paint, I ended up making ‘corncobs’. It seemed I had found a new way to express the invisible part of life.” Yet those paintings were not simple reproductions of natural objects. The human faces and bodies composed of corncobs that appeared in his paintings were just a means to dig into the procedures and techniques of creating forms. “What I was creating was a vast system,” says Pan Dehai, “characterized by diversity and integrity. Each part, each small single item, was just like a single cell, making up a symbiosis of self, birth, circulation and development. It seemed to have many eyes and many lungs, keeping a close relationship with the outside world while maintaining its own inner development logic.”

In the late 1980s, modernism and its related pursuit of “essence” were considered passé. New trends such as Cynical Realism and Chinese Political Pop were taking hold. Beijing was the young artists’ place of choice. The protective wings of the city’s foreign institutions offered them a sanctuary unavailable anywhere else in the country. In the provinces, the spirit of renewal did not extend beyond the art studios. For example, in Wuhan, Hubei province, Wang Guangyi’s much-taunted “great criticism” was a topic of discussion for only a select few. Yet Pan Dehai kept abreast of these developments and vaguely sensed that something was on in the Chinese art world—with its center in the capital. So in 1992, he decided to move to Beijing, where he was to stay for eight years.

Pan Dehai did not enter Beijing a “hero”. He kept a low profile at first. None of the contemporary art movements taking place there bore any relation to him. In fact, he went so unnoticed that his friends thought he had disappeared. Yet he was there and kept quietly working. He was now aware that “a style which lasts for too long is tantamount to suicide” (1990). And imperceptibly at first, his “corncobs” rapidly evolved into something else. They multiplied, in a natural way, and gradually took up an increasingly obvious human form, complete with nose and eyes. He was now back to figuration, explaining his process as follows: “If the image you depict is hard to identify, it is more likely to be ignored. The choice of symbols is of vital importance. I have used ‘corncobs’ for more than a dozen years. It is now time to move on.”

And moving on also meant not staying in Beijing. In 1999 he decided to move back to Kunming. Pan Dehai had indeed had a hard time in Beijing, where he had “lived a very unsteady life, moving house again and again, and never feeling he belonged to the trends.” Yet he had produced more and more paintings and by the time he was ready to leave the city, he could make a decent living solely by selling his works. So why did he go? For psychological reasons: because in Kunming, he had old friends, old memories and emotions, as well as sunshine and nature that could awaken his soul. Should he have stayed in Beijing or gone to Shanghai? Wasn’t performance art by then already changing the scope of Chinese art? Weren’t momentous institutional transformations, such as the meteoric growth of galleries and the arrival of foreign dealers, portending a better future for artists? Perhaps. But Pan Dehai wanted out; he wanted to be back in his beloved Kunming.

But once he found himself back in Kunming, things were not as his memory had registered them. “Many of my friends had changed,” he says, “they had become fatter, older, and balding. These changes were too ordinary to be noticed by people, but I noticed them.

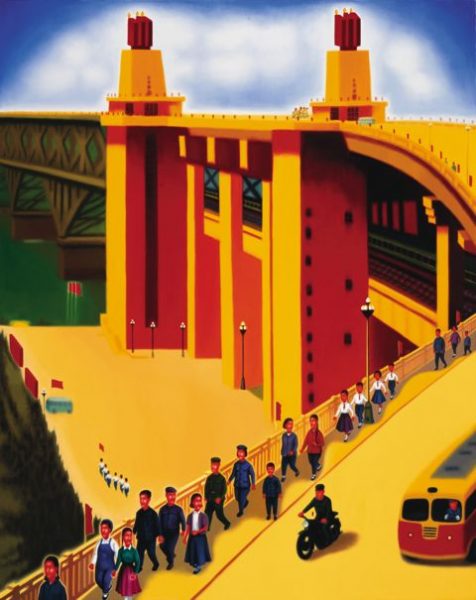

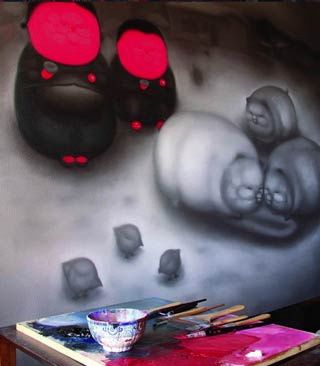

I represented those trivial details in my own way. Yet, I did not want it to be too sorrowful, so I let them have a relatively serene expression.” The result is the series, Less and Less Hair. His technique had changed. He was now back to oil painting and definitely back to figuration. His doubts were over. “Since the 1990s, money worship and materialism have completely occupied people’s minds; their desires are endless… As if everybody wanted to develop himself/herself into the biggest and the fattest. It is this new mentality that I translate into my Fatty series; I try to show that society has transformed all people, and given them a single unique face, as if they were bereft of any individual personality. And this happens amidst general indifference.”

Yet, Pan Dehai’s Fatty works were not monotonous. He discovered that he could combine the chubby figures with scenes borrowed from his memory of the countryside, or from images of social vicissitudes and revolutionary history. In his Metropolitan series, the “fatties” ride boats; they wear military uniforms and sit on horse-drawn carriages. Social references are paramount. In his treatment of these themes, Pan Dehai draws largely on his past experience among the poor and destitute. “In the ‘Vanity Fair’ of Beijing,” he says, “every day is a struggle for life, with very high pressure. People are restless and impatient. It is impossible for them to find the peace of mind necessary to think. Everything seems to be in a muddled rush, renting a house, eating meals, selling paintings, visiting people, keeping contacts, etc.”

Another series, the Acnes (Youthpox), drew on his memory of the Cultural Revolution. “I want to recall those images of life that have survived, just as dim as mist. In those years, we youngsters were just like a group of aimless souls wandering in the wilderness.” Yet, in Pan Dehai’s various series, there is always an underlying tone of humor. Be it when painting scenes behind the millstone, beside the stable or the fire, he always endeavors to be funny, because, “behind each joke, there are always a lot of things; they are simple in form, yet profound in meaning.”

At the end of the day, Pan Dehai does not feel he belongs to any trends, “As far as my own painting is concerned, since the ‘85 New Wave, I have never again been in the trends. Nevertheless, I still think my paintings are good.”

And he may well be right. Since the late 19th century, people have repeatedly tried to categorize art history into movements and styles. But paintings like those of Paul Klee, Marc Chagall and later, Balthus and others, have always been outside the mainstream of their times. Pan Dehai is no different. Like them, his only concern is for his own mode of pictorial language. And in this, his sole guide is the drift of his soul. It is only in this sense that his works warrant the name, “New Painting”.