Postmodernism is best understood by defining the modernist ethos it replaced – that of the avant-garde who were active from 1860s to the 1950s. The various artists in the modern period were driven by a radical and forward thinking approach, ideas of technological positivity, and grand narratives of Western domination and progress. The arrival of Neo-Dada and Pop art in post-war America marked the beginning of a reaction against this mindset that came to be known as postmodernism.

The reaction took on multiple artistic forms for the next four decades, including Conceptual art, Minimalism, Video art, Performance art, and Installation art. These movements are diverse and disparate but connected by certain characteristics: ironical and playful treatment of a fragmented subject, the breakdown of high and low culture hierarchies, undermining of concepts of authenticity and originality, and an emphasis on image and spectacle. Beyond these larger movements, many artists and less pronounced tendencies continue in the postmodern vein to this day.

Postmodernism is distinguished by a questioning of the master narratives that were embraced during the modern period, the most important being the notion that all progress – especially technological – is positive. By rejecting such narratives, postmodernists reject the idea that knowledge or history can be encompassed in totalizing theories, embracing instead the local, the contingent, and the temporary. Other narratives rejected by postmodernists include the idea of artistic development as goal-oriented, the notion that only men are artistic geniuses, and the colonialist assumption that non-white races are inferior. Thus, Feminist art and minority art that challenged canonical ways of thinking are often included under the rubric of postmodernism or seen as representations of it.

Postmodernism overturned the idea that there was one inherent meaning to a work of art or that this meaning was determined by the artist at the time of creation. Instead, the viewer became an important determiner of meaning, even allowed by some artists to participate in the work as in the case of some performance pieces. Other artists went further by creating works that required viewer intervention to create and/or complete the work. The Dada readymade had a marked influence on postmodernism in its questioning of authenticity and originality. Combined with the notion of appropriation, postmodernism often took the undermining of originality to the point of copyright infringement, even in the use of photographs with little or no alteration to the original.

In the Chinese art world, most postmodern artists were born after 1970s — the year of Mao Zedong’s death and the end of the Cultural Revolution — and they have been shaped by a liberalized education, globalization, and the dizzying growth of China’s economy. The big difference between their generation and their father is that they can freely choose what subject they want to do or what kind of idea they want to show people. the older generation could take only inspiration from society or the government.

A majority of these artists are products of the one-child policy, enacted in 1980. They are the Post-Mao generation, and their sense of difference is profound. The generation gap in China is so extreme, that between the parents of these artists and these young artists, it is as if they were born in two different countries in two different centuries.

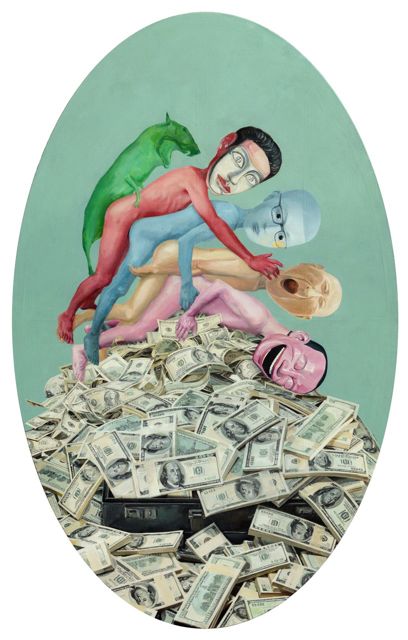

Such an example are the works by up & coming artist Wang Zi. Born in 1983, Wang Zi graduated from Tsinghua University in 2005 and has been involved in artistic creation since a decade ago. He reflects on problems, is engaged in the great debates in politics and culture and has his own views. In meetings and conversations with him, it will occur to you that between the 1970s generation and the young 1980s generation that Wang Zi belongs to, never having experienced the harsh and meagre existence that marked their childhood, they have no need to dissemble. The seek what is visually appealing and often challenged authority. They are unspoken and straightforward in their artistic expressions.

The varied works of Chinese postmodern artists not only reflect the depth of China’s generational divide, but also the younger generation’s embrace of Western Postmodernism’s aesthetic tropes and methodologies. Postmodern themes of individuality and personal identity are certainly present as are collective attempts to reach backwards and reclaim aspects of China’s deeply rooted culture that are worth sustaining and carrying forward. Remaining “Chinese” in the face of globalization is a major concern.

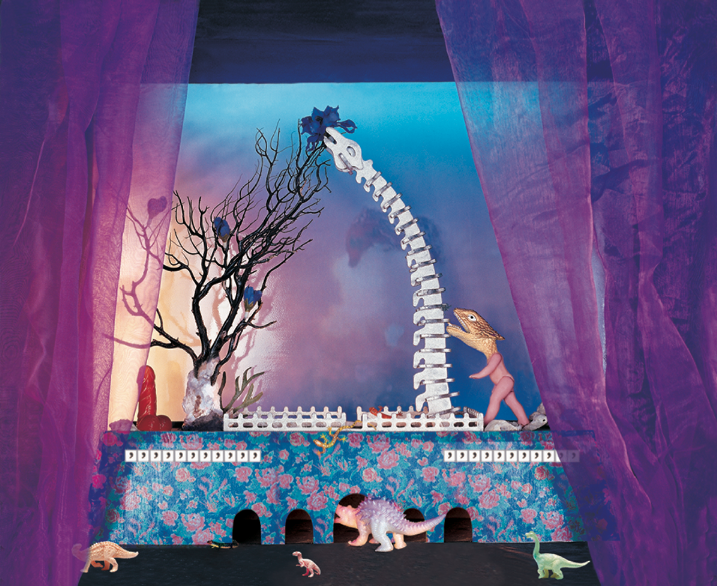

For established photographers Chen Zhuo + Huang Keyi, they integrate real and virtual images in their works, duplicating here and erasing there. In the process, they say, “some of our works become more real than reality, while others convert reality into fiction.” The ‘China Carnival’ and ‘Super Factory’ series not only portray the country as a frenzied fun park where Chairman Mao gives his blessing to roller-coaster riders, overseeing romantic love merging happily against a sky so blue to be true, but also marking the fast paced progress and to changes of the modern Chinese society.

China’s Post-Mao artists understand that for the first time there is some money to be made in showing and selling their work both in Asia and abroad. Ai Weiwei has shown that art world stardom may even be possible.

The idea of breaking down distinctions between high and low art, particularly with the incorporation of elements of popular culture, was also a key element of postmodernism that had its roots in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the work of Edgar Degas, for example, who painted on fans, and later in Cubism where Pablo Picasso often included the lyrics of popular songs on his canvases. This idea that all visual culture is not only equally valid, but that it can also be appreciated and enjoyed without any aesthetic training, undermines notions of value and artistic worth, much like the use of readymades.

Postmodernism cannot be described as a coherent movement and lacks definitive characteristics. It can be better understood instead as a set of styles and attitudes that were affiliated in their reaction against modernism. A new approach to popular culture and the mass media emerged in the 1950s, sparking a wave of art movements that reintroduced representation from disparate sources and experimented with image, spectacle, aesthetic codes, disciplinary boundaries, originality, and viewer involvement in ways that challenged previous definitions of art.