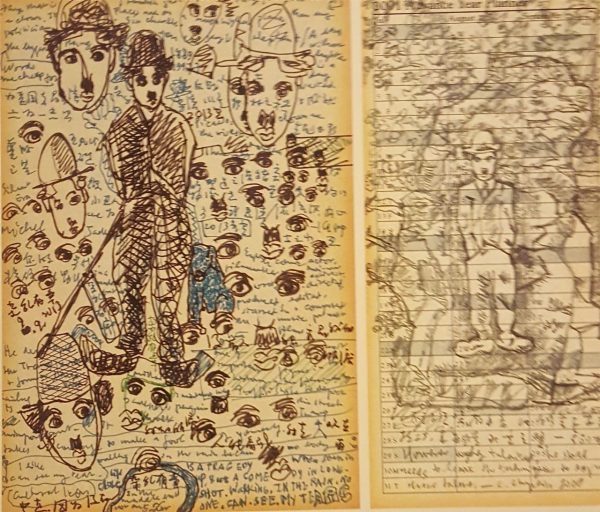

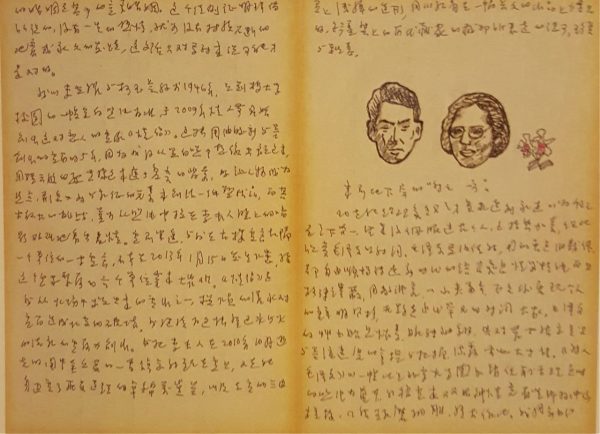

Renowned Singapore living art legend Tan Swie Hian is particular about his notebooks. They have to be A5 and leather-bound, and the paper inside must be newsprint paper, which he describes as “very good, very absorbent”. He gets them custom-made by his favourite printer.

To him, the importance of having the perfect notebook cannot be overstated. It serves as a conduit for and repository of his thoughts on art, politics, religion and society. Like all intelligent thoughts, they multiply, transform and cross-pollinate. And ultimately, a few become the basis for a new canvas or sculpture.

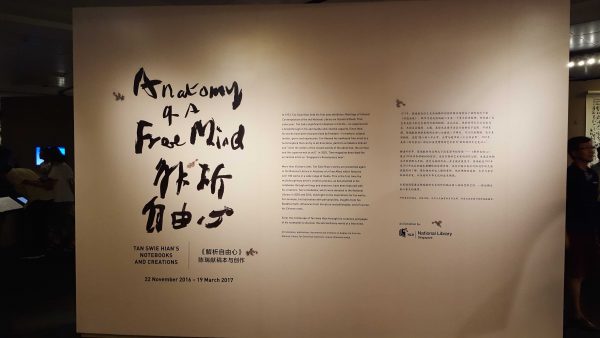

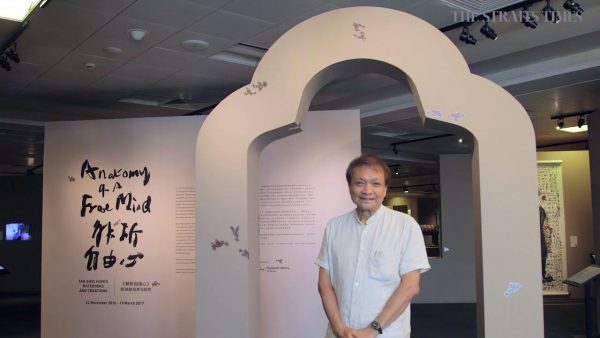

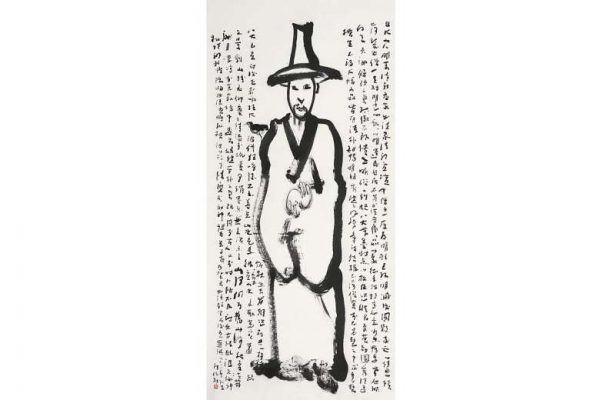

In December 2016, an exhibition ‘Anatomy of a Free Mind: Tan Swie Hian’s Notebooks & Creations’, centred on Tan’s notebooks opened at the 10th floor of the National Library Building. It is organised in “clusters” – each cluster features specific pages of the notebooks which have culminated in significant artworks, which will also be on display.

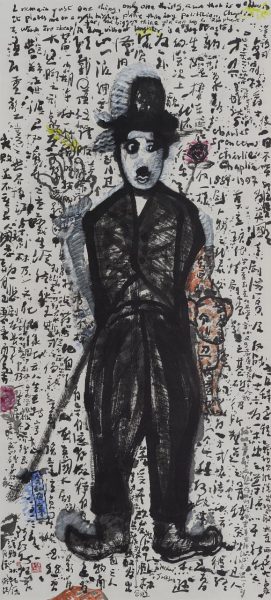

The famous artworks include Tan’s massive painting of Mr and Mrs Lee Kuan Yew, a portrait of Charlie Chaplin, and a series of lithographs inspired by Nelson Mandela. There is also the painting White Horse & Reed Flowers, which grew out of his poem and into a sketch and later a painting.

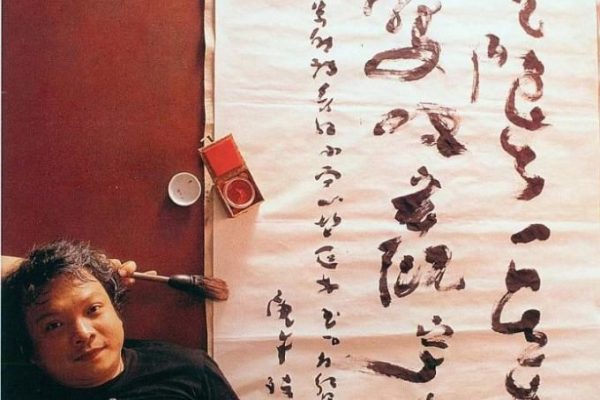

At his studio in Telok Kurau, Tan is eager to explain his methods. He says: “I’ve been writing journals and notebooks for the past 50 years, and this is the first time they are being displayed. To have to select pages from a big stack of 40-odd notebooks has been quite daunting.”

His current notebook shows copious jottings on his recent trip to Kyoto for the World Forum on Sports and Culture, a National Geographic story on a remote Pakistani region of Gojal that captivated him, and other moments and events.

“I delivered a speech in Kyoto and painted a six-foot painting in front of a crowd of dignitaries, celebs and journalists. It was so taxing being watched as you work. But there was a Japanese tea ceremony in which they served these wagashi (local confections made from plant ingredients). They were so intricately crafted that I drew them in my notebooks.”

His sketches of the wagashi accompanied by notes on the side gradually transform over the next few pages into an Earth-like image, before mutating once again into several pictures of hands with entwined fingers: “These hands are a mudra, a symbolic gesture in Hinduism and Buddhism. But I’m trying to see how to encompass all these ideas to make them my own. It’s still in flux.”

His jottings appear in prose and in verse, in English and Chinese. Sometimes, he writes them first in English, only to translate them later into Chinese. He explains: “I enjoy the mental gymnastics of translation.” This is not a man who takes many shortcuts.

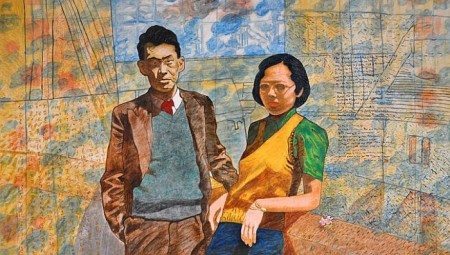

One of his ideas took a long reflection period which lasted even after the artwork was complete. That was A Couple, a massive 2.9m by 5.6m painting that featured Mr and Mrs Lee as a young couple in Cambridge University. Tan says: “I have long admired Mrs Lee as a paragon of virtue. And I think of their marriage as something extraordinary. So on Valentine’s Day 2009, I embarked on painting the couple, in hope that people can emulate them.”

But when Mrs Lee died in 2010, Tan wrote a poem, inscribed it on the painting and added two Vanda “Miss Joaquim” orchids by her side.

Three years later, a fire broke out near Tan’s studio and the water from the fire engine wrecked the painting. Instead of starting a new one, he cleaned and restored the work, describing it as one that has “undergone baptism of water and fire”.

But just as Mr and Mrs Lee endured the ages, Tan expects the painting too to transcend time. He adds: “A great piece of art is capable of adjusting itself according to the psychological background and intellectual and intuitive abilities of the viewer. It is a living thing, an organism that stirs and moves the viewer. It does not stay as just one thing.”

*article extracted from the Business Times