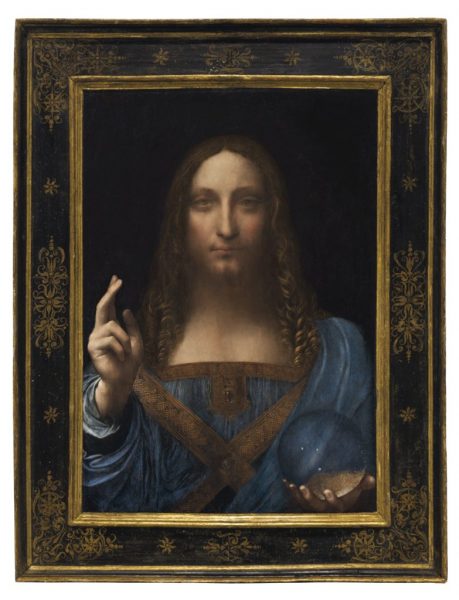

After weeks of anticipation, it finally happened: Leonardo da Vinci’s: Salvator Mundi (circa 1500), billed as the last known painting by the Renaissance master in private hands, sold at Christie’s for $450.3 million. It is, by far, the most expensive work of art ever sold at auction. In fact, the price is more than double the next most expensive work ever sold, Picasso’s Les femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’), which fetched $179.4 million in 2015.

The work went to an anonymous client. Before a packed salesroom and scores of camera phones held aloft, bidding opened at $70 million. At $190 million, five bidders—four on the phones and one in the room—were still chasing the painting.

After a protracted bidding war in which a bidder continued to bid in increments as large as $30 million—and another bid in smaller steps of around $2–5 million—the work hammered down for $400 million to a flurry of applause (and a few gasps). With the auction house’s fees, the final price was $450.3 million.

The painting was one of 58 works included in Christie’s evening sale of postwar and contemporary art on Wednesday at Rockefeller Center in New York.

Salvator Mundi was consigned by the Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev, who bought it in 2013. At tonight’s sale, the work carried a guarantee by a third party, which means that an outside buyer had essentially committed to purchase the painting in advance for $100 million. (In exchange for the early commitment, the guarantor will receive a share of the profits above $100 million.)

The auction house took the unusual move of placing the work in its evening contemporary art auction, essentially betting that it would appeal to the biggest trophy-hunting art collectors regardless of when it was made. And indeed, the battle eventually came down to an Old Master specialist (De Poortere) and a contemporary one (Rotter), with the latter emerging victorious after a long sequence of aggressive bids.

Until now, the most expensive painting ever sold at auction was Pablo Picasso’s Les femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’) (1955), which was sold at Christie’s in May 2015 for $179.4 million. (Accounting for inflation, the price is around $186 million in 2017 dollars.)

And though it was included in the contemporary sale, Salvator Mundi also easily become the most expensive Old Master painting ever sold at auction. It broke the record set by Peter Paul Ruben’s Massacre of the Innocents (1612), which fetched $76.7 million (equivalent to $106 million today) at Sotheby’s in 2002.

The Leonardo painting has a background story that involves a royal family, an estate sale, and a contentious lawsuit. Originally commissioned for the French Royal collection, it went missing for decades. In 2005, a consortium of dealers spotted the painting at an estate sale and had it authenticated as a bona fide Leonardo. In 2013, they sold the work to Swiss dealer and so-called “freeport king” Yves Bouvier for a price reportedly between $75 million and $80 million.

Bouvier then flipped the work to Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev for a reported $127.5 million. The colossal mark-up eventually touched off a contentious legal battle between the two men that is still ongoing.

Restoration issues are believed to have influenced the lower offering price at Christie’s—$27.5 million less than Rybolovlev paid. The damaged work was heavily restored ahead of its debut in a Leonardo exhibition at the National Gallery in London in 2012.

News of the painting’s sale set off something of a Leonardo frenzy. It attracted lines around the block on nearly every stop of its promotional world tour, including in London and San Francisco. Nearly 27,000 people came to see the painting.

Fascination with the painting sparked a flood of stories about the mysterious orb and what motivated Leonardo, an avid student of optics, to render it with less than 100 percent accuracy.

The painting has sold for more money than most people could ever imagine.

*extracted from artnet.com