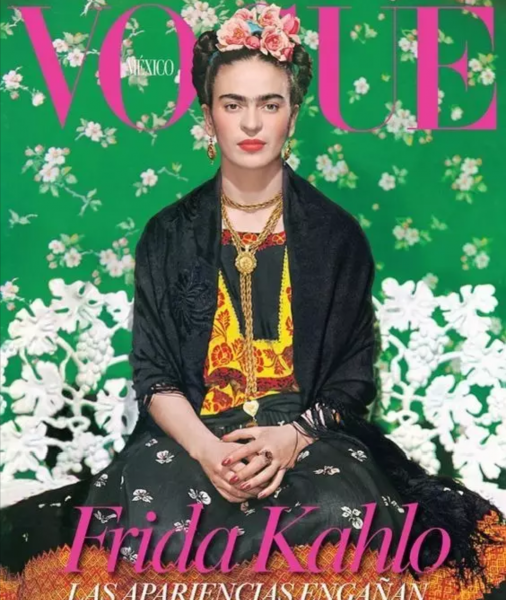

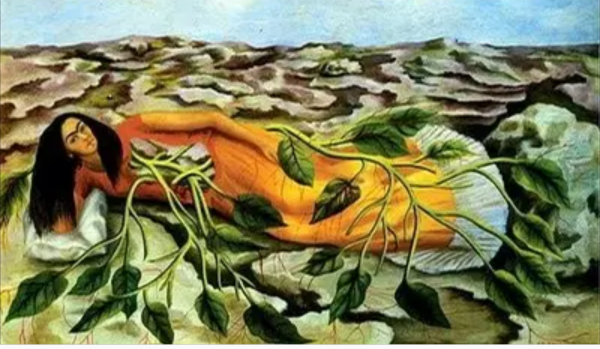

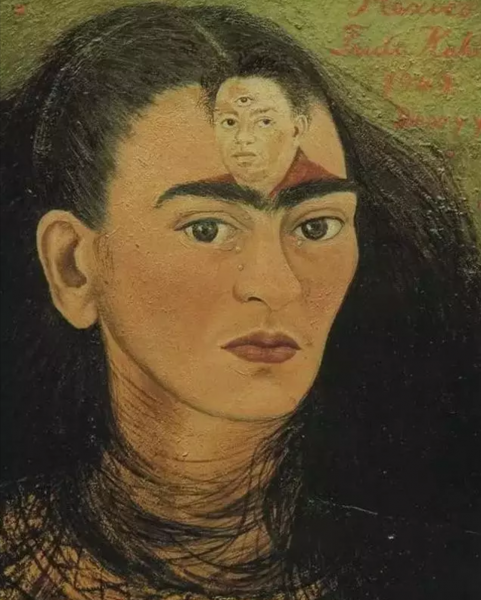

Considered one of the Mexico’s greatest artist, Frida Khalo was born on July 6, 1907 in Coyocoan, Mexico City, Mexico. She was the first Latin American artist to break the $1 million mark at auction, in May 1990, when Sotheby’s sold ‘Diego y Yo (1949)’, for $1.4 million (on an estimate of $800,000 to $1 million). … The record for a Frida Khalo painting at auction is $5.6 million set at Sotheby’s New York in 2006 for Roots (1943).

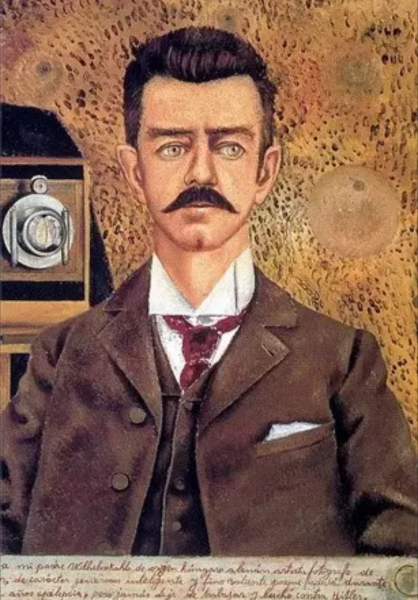

She grew up in the family’s home where was later referred as the Blue House or Casa Azul. He father is a German descendant and photographer. He immigrated to Mexico where he met and married her mother Matilde. Her mother is half Amerindian and half Spanish. Frida Kahlo has two older sisters and one younger sister.

Frida Kahlo has poor health in her childhood. She contracted polio at age of 6 and had to be bedridden for nine months. This disease caused her right leg and food grow much thinner than her left one. She limped after she recovered from the polio. She has been wearing long skirts to cover that for the rest of her life. Her father encouraged her to do lots of sports to help her recover. She played soccer, went swimming, and even did wrestle, which is very unusual at that time for a girl. She has kept a very close relationship with her father for her whole life.

On September 17, 1925, an accident would transform her life forever. Frida was 18.

It was a gray day. A light rain had just fallen. After spending the afternoon wandering among the street stalls of downtown Mexico City, Frida and her then boyfriend Alex Gomez Arias caught a bus that would take them home to Coyoacán. The new bus was brightly painted with two benches along the sides. It was nearly full but Alex and Frida found seats together near the back. The bus driver sped off to cross the busy streets on his way out of town.

The electric train [streetcar] with two cars approached the bus slowly. It hit the bus in the middle. Slowly the train pushed the bus. The bus had a strange elasticity. It bent more and more, but for a time it did not break. It was a bus with long benches on either side. I remember that at one moment my knees touched the knees of the person sitting opposite me. I was sitting next to Frida. When the bus reached its maximal flexibility it burst into a thousand pieces, and the train kept moving. It ran over many people.

I remained under the train. Not Frida. But among the iron rods of the train, the handrail broke and went through Frida from one side to the other at the level of the pelvis.”

Frida said that the “handrail pierced me the way a sword pierces a bull.”

Alex continues: When I was able to stand up, I got out from under the train. I had no lesions, only contusions. Naturally the first thing that I did was to look for Frida. Something strange had happened. Frida was totally nude. The collision had unfastened her clothes. Someone in the bus, probably a house painter, had been carrying a packet of powdered gold. This package broke, and the gold fell all over the bleeding body of Frida. When people saw her, they cried, ‘La bailarina, la bailarina!’ With the gold on her red, bloody body, they thought she was a dancer.

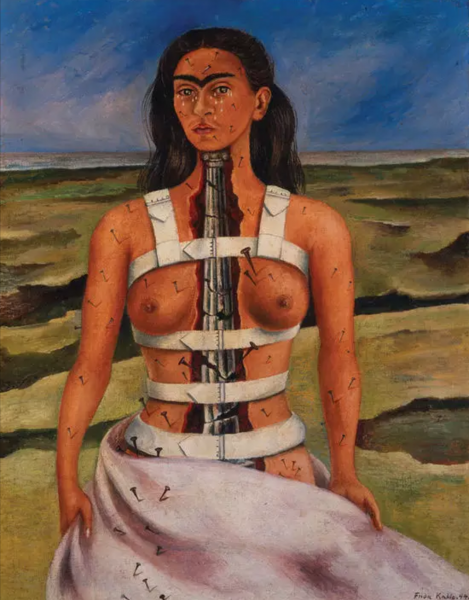

Frida’s condition was so grave doctors didn’t believe they could save her. They thought she would die on the operating table. Her spinal column was broken in three places in the lumbar region. Her collarbone was broken and her third and fourth ribs. Her right leg had eleven fractures and her right foot was dislocated and crushed. Her left shoulder was out of joint, her pelvis broken in three places. The steel handrail produced a deep abdominal wound, entering through the left hip and exiting through the genitals. She convalesced for two years though she would never fully recover.

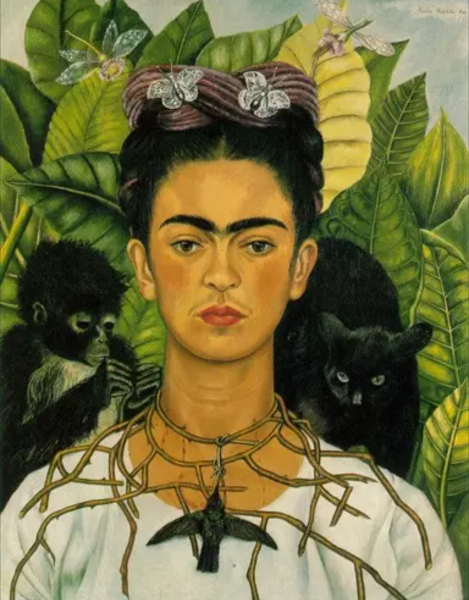

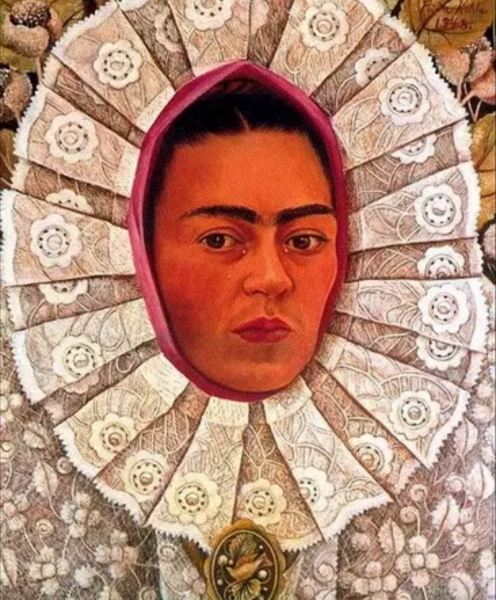

To kill the time and alleviate the pain, she started painting and finished her first self-portrait the following year. Frida Kahlo once said, “I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best”. Her parents encouraged her to paint and made a special easel made for her so she could paint in bed. They also gave her brushes and boxes of paints.

An Unconventional Union

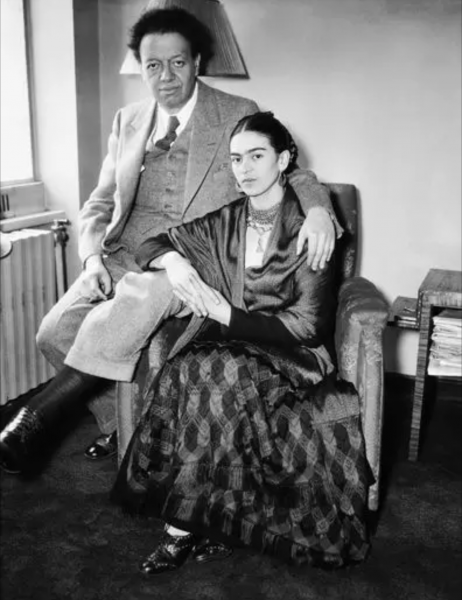

No matter whether she was in Paris, New York or Coyoacán, she clothed herself elaborately in the Tehuana costumes of Indian maidens. As much as Frida’s country defined her, so, too, did her husband, the celebrated muralist, Diego Rivera. If Mexico was her parent, then Rivera – 20 years her senior – was her “big-child.” She often referred to him as her baby. She met him while still a schoolgirl and later, in 1929, became the third wife of a man who gaily accepted the diagnosis of his doctor that he was “unfit for monogamy.”

Needless to say, theirs was an unconventional and problematic, if passionate, union that survived numerous affairs (on both their parts), separations and even a divorce in 1939 and subsequent remarriage in 1940. Their love proved hardy, like the roots in Frida’s painting “The Love Embrace.” But Frida’s hold on Diego as a husband was tenuous. Marriage was hardly a salve for the suffering that had characterized Frida’s young life – a horrific trolley car accident left her broken as a youth and debilitated throughout much of her adulthood. Diego’s incorrigible philandering – once with Frida’s own younger sister, Cristina – only exacerbated her pain. “I suffered two grave accidents in my life,” she once said, “One in which a streetcar knocked me down … The other accident is Diego.”

“I did not know it then, but Frida has already become the most important fact in my life. And she would continue to be, up to the moment she died….” -Diego Rivera

The Meeting

The invisible voice continued to play pranks on Rivera until it finally presented itself in the mischievous flesh: One night, as Rivera was painting up on the scaffolding and his then-wife Guadalupe “Lupe” Marín was working below, they heard loud commotion coming from a group of students pushing against the auditorium door. Rivera describes the moment, which he would only later, in hindsight, come to recognize as pivotal in his life:

All at once the door flew open, and a girl who seemed to be no more than ten or twelve* was propelled inside.

She was dressed like any other high school student but her manner immediately set her apart. She had unusual dignity and self-assurance, and there was a strange fire in her eyes. Her beauty was that of a child, yet her breasts were well developed.

She looked straight up at me. “Would it cause you any annoyance if I watched you at work?” she asked.

“No, young lady, I’d be charmed,” I said.

She sat down and watched me silently, her eyes riveted on every move of my paint brush. After a few hours, Lupe’s jealousy was aroused, and she began to insult the girl. But the girl paid no attention to her. This, of course, enraged Lupe the more. Hands on hips, Lupe walked toward the girl and confronted her belligerently. The girl merely stiffened and returned Lupe’s stare without a word.

Visibly amazed, Lupe glared at her a long time, then smiled, and in a tone of grudging admiration, said to me, “Look at that girl! Small as she is, she does not fear a tall, strong woman like me. I really like her.”

The girl stayed about three hours. When she left, she said only, “Good night.” A year later I learned that she was the hidden owner of the voice which had come from behind the pillar and that her name was Frida Kahlo. But I had no idea that she would one day be my wife.

As a couple, the Riveras remained childless; this, as much as Diego’s infidelities, was a source of great anguish for Frida for whom Diego was everything: “my child, my lover, my universe.”

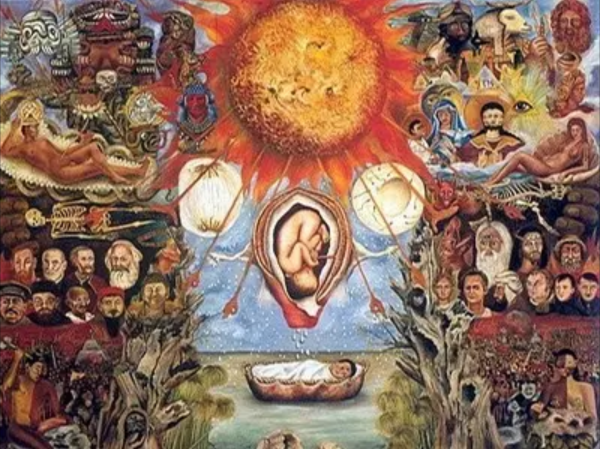

As individual artists, the pair was wildly productive. Each regarded the other as Mexico’s greatest painter. Frida referred to Diego as the “architect of life.” Each took a deep, proprietary pride in the other’s creations, drastically different as they were in habit and style.

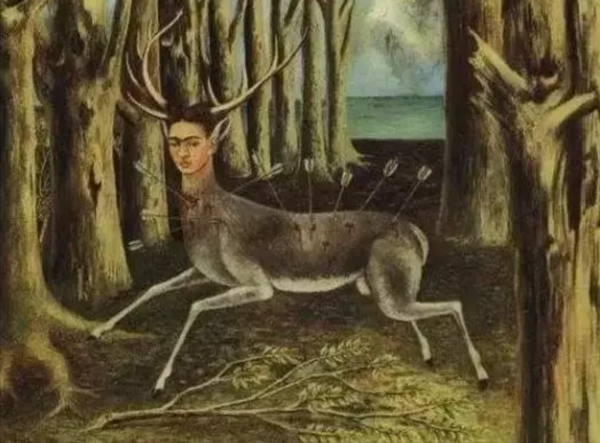

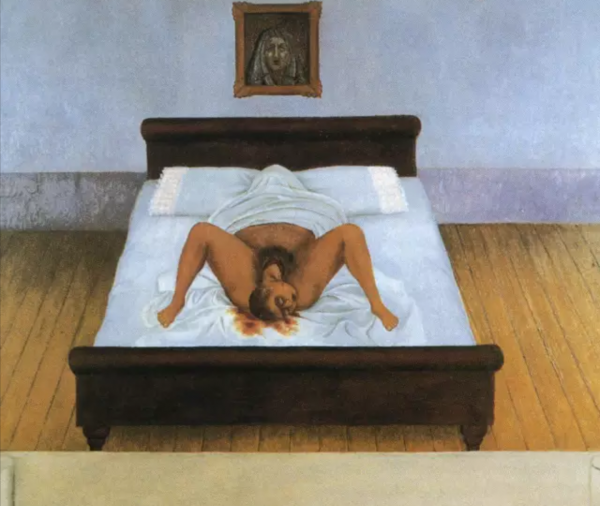

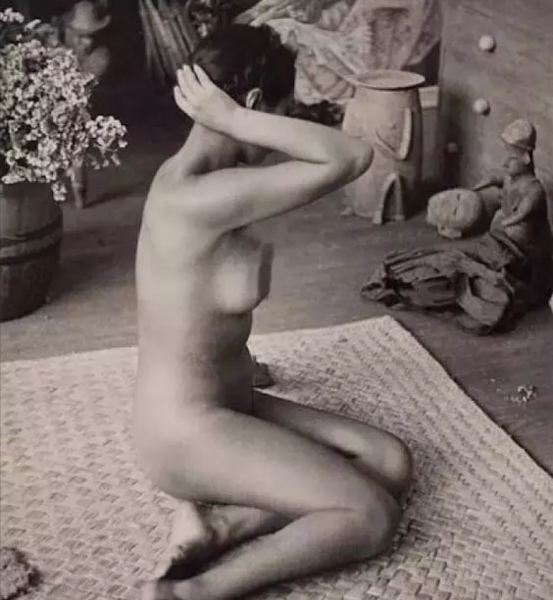

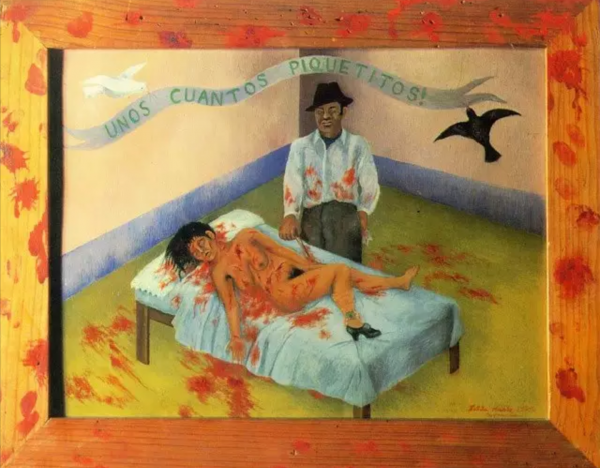

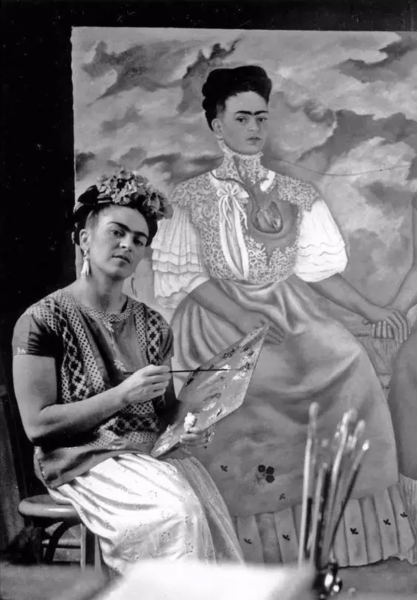

On a high scaffold in the outdoors, the driven Diego painted for days on end. He loved painting as obsessively as Frida loved him, rendering grand public murals with political themes. Frida, meanwhile, was often immobilized in a cast in her bed, or confined to a hospital room, either anticipating a surgery or recovering from one. She alternately languished and painted intensely personal works. About a third of her entire body of work – about 55 paintings – consists of self-portraits. In some, she stares out, willfully impassive, her face mask-like; in others, graphic depictions of her internal bodily organs reveal corresponding states of mind. She shied away from nothing, revealing – indeed, reveling in – the indignity of heartbreak, as well as the gut-wrenching pain of abortion and miscarriage.

Diego, a social realist, actually welled up with tears of pride when Picasso once admired the eyes in a painting of Frida’s. And he wrote this glowing recommendation to a friend about an early exhibition of her work: “I recommend her to you, not as a husband but as an enthusiastic admirer of her work, acid and tender, hard as steel and delicate and fine as a butterfly’s wing, loveable as a beautiful smile, and profound and cruel as the bitterness of life.”

Career

In 1938, Frida Kahlo became friend of Andre Breton, who is one of the primary figures of Surrealism movement. Frida said she never considered herself as a Surrealist “until André Breton came to Mexico and told me I was one.” She also wrote, “Really I do not know whether my paintings are surrealist or not, but I do know that they are the frankest expression of myself”. “Since my subjects have always been my sensations, my states of mind and the profound reactions that life has been producing in me, I have frequently objectified all this in figures of myself, which were the most sincere and real thing that I could do in order to express what I felt inside and outside of myself.”

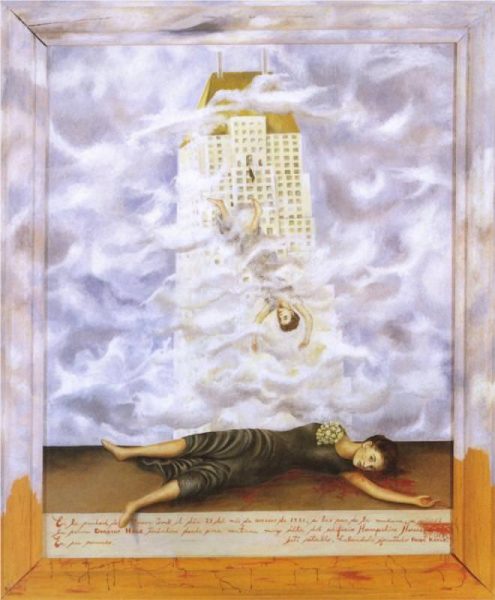

In the same year, she had an exhibition at New York City gallery. She sold some of her paintings and got two commissions. One of that is from Clare Boothe Luce to paint her friend Dorothy Hale who committed suicide. She painted ‘The Suicide of Dorothy Hale (1939)’, which tells the story of Dorothy’s tragic leap. The patron Luce was horrified and almost destroyed this painting.

The next year, 1939, Kahlo was invited by Andre Breton and went to Paris. Her works are exhibited there and she is befriended with artists such as Marc Chagall, Piet Mondrian and Pablo Picasso. She and Rivera got divorced that year and she painted one of her most famous painting, ‘The Two Frida’ (1939).

But soon Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera remarried in 1940. The second marriage is about the same as the first one. They still keep separate lives and houses. Both of them had infidelities with other people during the marriage. Kahlo received a commission from the Mexican government for five portraits of important Mexican women in 1941, but she was unable to finish the project. She lost her beloved father that year and continued to suffer from chronic health problems. Despite her personal challenges, her work continued to grow in popularity and was included in numerous group shows around this time.

In the year of 1944, Frida Kahlo painted one of her most famous portrait, ‘The Broken Column’. In this painting she depicted herself naked and split down the middle. Her spine are shattered like column. She wears a surgical brace and there are nails all through her body, which is the indication of the consistent pain she went through. In this painting, Frida expressed her physical challenges by her art. During that time, she had a few surgeries and had to wear special corsets to protect her back spine. She seeks lots of medical treatment for her chronic pain but nothing really worked.

Her health condition has been worsening in 1950. That year she was diagnosed with gangrene in her right foot. She became bedridden for the next nine month and had to stay in hospital and had several surgeries. But with great persistence, Frida Kahlo continued to work and paint. In the year of 1953, she had a solo exhibition in Mexican. Although she had limited mobility at that time, she showed up on the exhibition’s opening ceremony. She arrived by ambulance, and welcomed the attendees, celebrated the ceremony in a bed the gallery set up for her. A few months later, she had to accept another surgery. Part of her right leg got amputated to stop the gangrene.

With the poor physical condition, she is also deeply depressed. She even had a inclination for suicide. Frida Kahlo has been out and in hospital during that year. But despite her health issues, she has been active with the political movement. She showed up at the demonstration against US backed overthrow of President Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala on July 2. This is her last public appearance. About one week after her 47th birthday, Frida Kahlo passed away at her beloved Bule House. She was publicly reported to die of a pulmonary embolism, but there are speculation which was saying she died of a possible suicide.

Frida Kahlo’s fame has been growing after her death. Her Blue House was opened as a museum in the year of 1958. In 1970s the interest on her work and life are renewed due to the feminist movement, since she was viewed as an icon of female creativity. In 1983, Hayden Herrera published his book on her, A Biography of Frida Kahlo, which drew more attention from the public to this great artist. In the year of 2002, a movie named Frida was released, staring alma Hayek as Frida Kahlo and Alfred Molina as Diego Rivera. This movie was nominated for six Academy Awards and won for Best Makeup and Original Score.

She once wrote to a former lover (who allegedly had jilted her because of her physical infirmities), “you deserve the best, the very best, because you are one of the few people in this lousy world who are honest to themselves, and that is the only thing that really counts.”

When Frida Kahlo died, she left paintings, each of which corresponds to her evolving persona, as well as a collection of effusive letters to lovers and friends, and colorfully candid journal entries. All are irrefutable evidence that her life was nothing less than a quest to be honest to herself.