Lots of museum leaders talk about wanting to diversify their collections. Christopher Bedford, the director of the Baltimore Museum of Art, is actually doing it—though not everyone may agree with his tactics.

The Baltimore Museum of Art in Maryland, USA, is home to an internationally renowned collection of 19th-century, modern, and contemporary art. Founded in 1914 with a single painting, the BMA today has 95000 works of art—including the largest holding of works by Henri Matisse in the world.

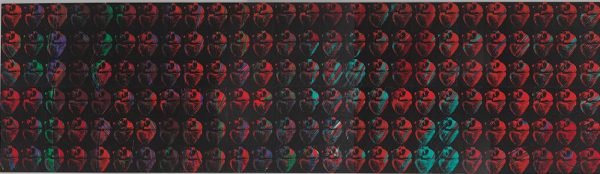

Next month, the museum is due to sell off seven works from its collection by Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and other 20th-century titans. The proceeds from the sale of these works by white male artists—a sum that could exceed $12 million—will be used to create a “war chest” to fund future acquisitions of cutting-edge contemporary art, specifically by women and artists of color.

Bedford says the move will be “absolutely transformative” for a collection that has woefully underrepresented non-white artists. It also comes at a “historically significant moment,” he says.

A Race to Catch Up

In recent years, museums across the globe have sought to explore new realms in their collections, snapping up works by upcoming artists of different ethnicities that allow them to tell a more complete story of Modernism.

“The decision to do this rests very strongly on my commitment to rewrite the postwar canon,” Bedford said. And while institutions sell art to fund new acquisitions every so often, the BMA’s latest deaccession stands out. While museums usually sell work to trade up, angling for major pieces by the hottest artists, the BMA is instead expanding out, redirecting the funds to correct the historical record. “To state it explicitly and act on it with discipline—there is no question that is an unusual and radical act to take,” Bedford says.

Institutions like the BMA are also eager to acquire work by rapidly rising contemporary art stars before they skyrocket out of reach.

The Decision to Deaccession

Deaccessioning—even when the proceeds are used to acquire more art—can sometimes be met with strong criticism from those who believe museums should not mortgage their history to cash in on current fashions. But without selling work from the collection, “I did not see a way to fulfill all of our capital aspirations, exhibition-making aspirations, and raise money to be competitive in the contemporary art market,” Bedford says. “It wasn’t a possibility.”

At the same time, Bedford felt the museum would struggle to remain relevant to its constituents if it did not make a meaningful commitment to inject its collection with new names.

“I don’t think it’s reasonable or appropriate for a museum like the BMA to speak to a city unless we reflect our constituents,” he says. “I think we are in a fortunate historical moment in that my existential urge to do something that matters, the constitution of Baltimore, and the most important artists working today all come together.”

The deaccession process began around a year ago, when Bedford asked Kristen Hileman, the museum’s longtime curator of contemporary art, to take a “hard look” at the collection and identify any promising candidates. She sought to identify works that were rarely shown due to their size or condition as well as objects that were inferior to other examples by the same artist already in the collection.

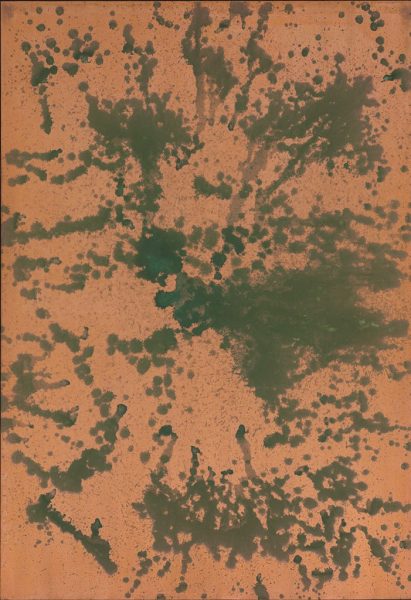

In the end, she chose seven works, including a 1979 Rauschenberg mural that was too large to show regularly and a 1956 dark-green-and-cream painting by Franz Kline that, while striking, was deemed less consequential than a second color Kline from 1961 that the museum regularly keeps on view. All the works slated for deaccession were acquired between 1986 and 1996.

Next came a rigorous approval process. The plan was presented to the board’s executive committee, every member of the museum’s curatorial staff, and the contemporary acquisitions committee, which is made up of local constituents and artists. “Had there been any dissenting opinions, we would have had to note that as the plan moved on to the next step,” Bedford says. The director also held one-on-one and group feedback sessions with interested trustees and committee members to discuss his rationale. Finally, in February, the entire board of trustees voted unanimously to approve the sale of all seven works.

Where Does the Money Go?

The BMA has opted to divide the proceeds from the sale into two buckets. The money generated by five of the works will be put into a dedicated endowment for contemporary art, of which the museum can spend around five percent each year. “I want to make sure my successor has a sizable war chest to continue the mission,” Bedford says.

Meanwhile, proceeds from the two Warhol works (one of which is expected to sell for between $2 million and $3 million at auction and one that will be sold via private sale) will be put into a fund that is designed to be spent sooner—over the next three to five years.

This move required the museum to seek the permission of the original donors of the Warhols: the Andy Warhol Foundation and collector Richard Pearlstone, who donated them together as part of a novel gift/purchase agreement the foundation made available to museums in 1994.

The president of the Warhol Foundation, Joel Wachs, says he was “happy to support the request because the funds will be used for a commendable purpose, and the Baltimore Museum will still have significant Warhol holdings which they have regularly exhibited.”

Pearlstone’s wife, Amy Elias, who is on the board of the BMA, agrees. “It took us about 30 seconds to say yes,” she told artnet News. Those who oppose deaccessioning might ask why donors are not simply kicking in more money to fund the BMA’s acquisitions instead, but Elias threw cold water on that argument. “I don’t know if that’s realistic,” she says. “While we do work hard to fundraise, there’s a limited pool.”