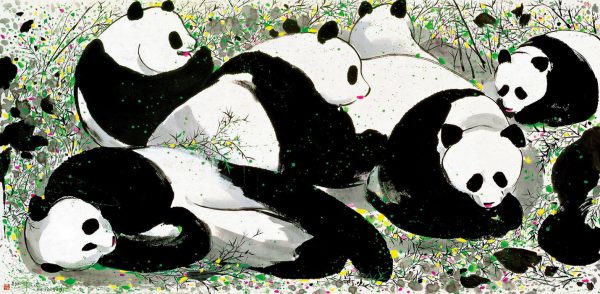

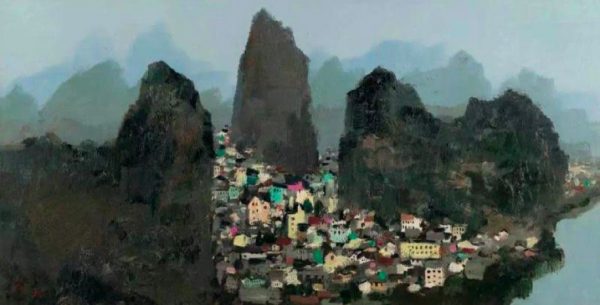

Wu Guanzhong, arguably one of the most important Chinese artists of the 20th century, has given the Singapore Art Museum his largest donation to a public museum comprising 113 oil and ink works painted during the years 1957 to 2007. These works represent Wu’s oeuvre over five decades and in both the oil and ink mediums. Although Wu Guanzhong did not begin to paint in ink in an intense way until 1974 when he was 55 years old, the thinking in oil and ink started at the very beginning of his artistic career. Wu also painted in watercolour, mainly during the early phase of the 1950s and 1960s.

A key significance of Wu Guanzhong is the crossing and synthesising of the oil and ink art forms. If the story of 20th century Chinese art is a journey anchored in the intersections of oil and ink, western and traditional Chinese art, Wu Guanzhong stands right in the middle of these crossings.

The term ‘decussation’ in physiology refers to the crossing of nerve tracts in the human brain. In botany, the term refers to leaves arranged along a stem in pairs, forming shapes of an X. Oil and ink in art are not just about colour pigments and painting instruments: they represent cultural make-up complete with philosophical outlook, aesthetic value, theory and history, the interchanges of which in the course of the 20th century are akin to a stem of leaves forming in decussation, creating a new spectacle of intercultural brilliance. This could not have happened any earlier due to limited cross-cultural exchanges prior to this time. The relations between ink painting and global modern art have been a topic of particular concern in recent Chinese art discourse.

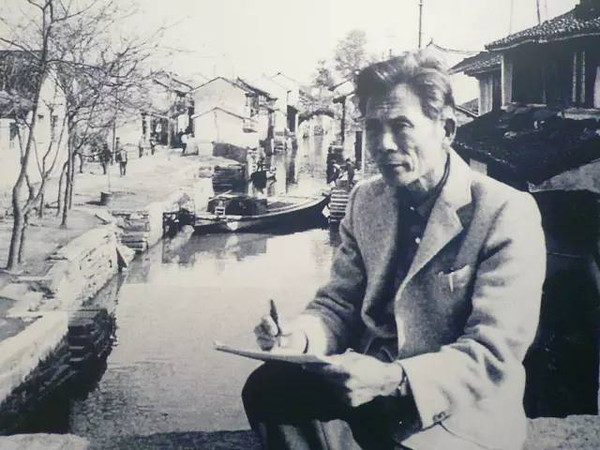

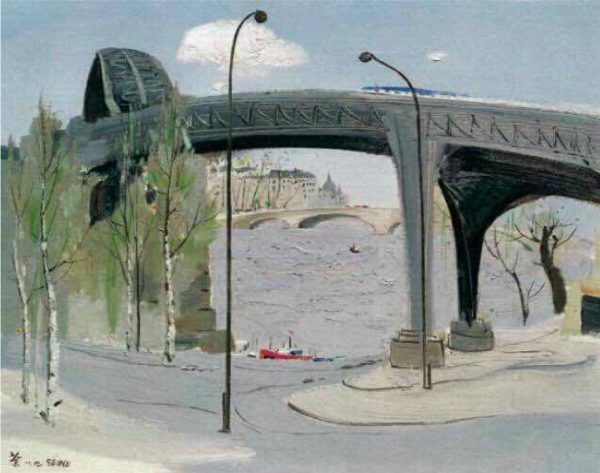

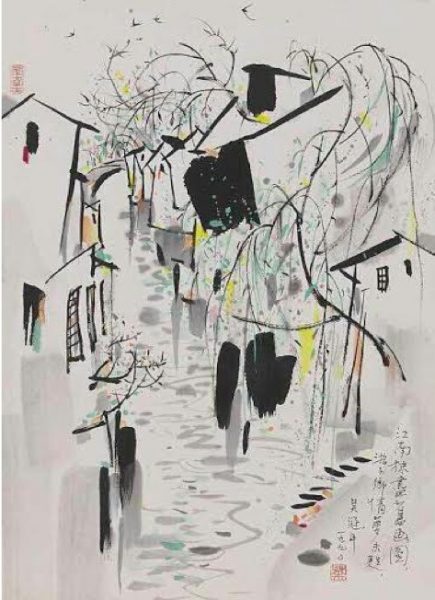

Born in 1919, Wu Guanzhong trained in oil and ink painting at the China Art Academy (1938–42) and subsequently at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux- Arts in Paris. Wu worked primarily in oil from the 1950s to 1974 with some watercolour in the early part of this period. He painted in ink in a serious manner only after 1974. A small ink painting from that year on the cityscape of Chongqing marked the beginning of this new phase of dual medium. Wu later wrote, “This miniature work was the entrepôt of my journeys in oil and ink.” This moment of ‘entrepôt,’ which happened towards the closure of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, was to be a great revelation in Wu Guanzhong’s artistic career.

‘Entrepôt’ incidentally, is also a word that describes Singapore’s historical, geographical and cultural disposition as a crossroads. Wu Guanzhong first stepped foot onto Singapore’s Clifford Pier, a transit point during his sea voyage to France, in 1947. Despite having always wanted to visit Singapore, he was not impressed, writing that Singapore was “a backward town, with some hawkers selling sliced pineapples, with flies hovering all over.” Some 60 years later, in a further decussation, Wu decided to give his largest donation of artworks to Singapore.

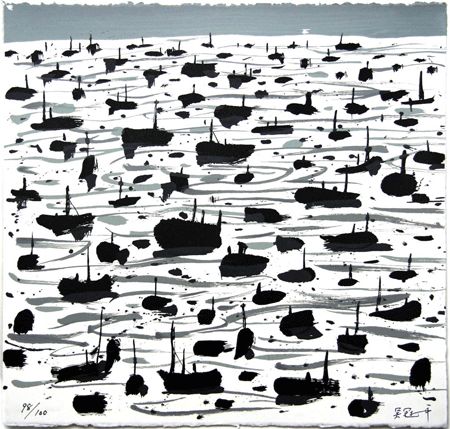

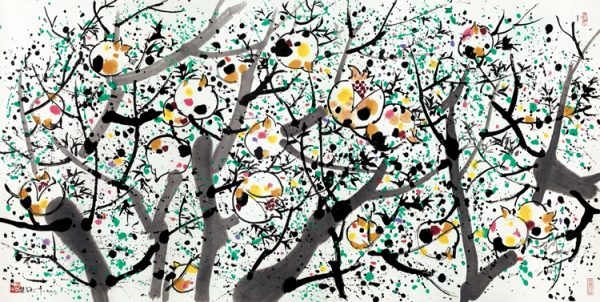

The relationship between oil and ink is key to understanding Wu Guanzhong’s work. Art scholars have observed that Wu impregnated his oil with ink aesthetics and ink with formalism in western art. James Cahill in an article co-authored with Cao Xingyuan noted that Wu Guanzhong synthesised the forms rendered through contour outline in traditional Chinese ink painting, and forms delineated through clear, flat and curvilinear lines in western artists like Matisse, Picasso and Miro, to create Wu’s own style of crisscrossing and repetitious lines such as in his painting of old trees. This is an example of Wu’s virtuosity in drawing inspiration from both Chinese and western art.

Practically all of Wu Guanzhong’s works can be discussed within this matrix of interrelations between oil and ink, with watercolour as an interfacing category. Wu’s early explorations of aesthetics and techniques between oil and ink were done in watercolour; the water and paper-based medium offers opportunities of linear quality with large void areas of ink painting and the multiplicity of colours and compositional design of oil painting.

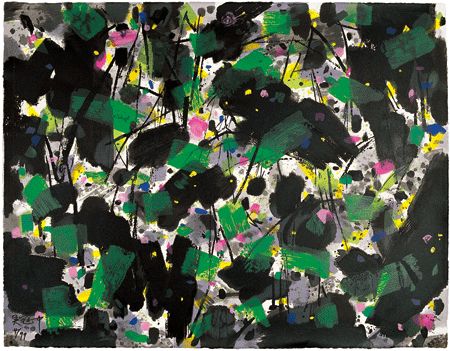

Wu notes that by the 1980s he was painting primarily in ink, but that four decades of oil painting turned out to be a stepping stone for ink. Oil and ink were his double-edged sword, a window to his decussation of cultures. Oil and ink are not merely mediums and techniques; interfacing Wu’s paintings with his writings and broader aesthetic and cultural histories and concerns, enable us to paint a picture of intercultural splendor.

At a recent conference in Singapore, Michael Sullivan, a Western authority on modern Chinese art history and criticism, singled out Van Gogh and Wu Guanzhong, exemplified by the former’s letters to his brother Theo, and the latter’s critical writings, as rare examples of artists who are deeply thoughtful and articulate with both the brush and the pen.

Form

When published in 1978, Wu Guanzhong’s essay Formal Beauty of Painting caused a stir in the immediate post- Cultural Revolution period as the artist annunciated his opposition to three decades of social realist persuasion. Cai Yi, in his New Aesthetics, published in 1947, predicated the theoretical foundation for social realism in China.

Form to Cai Yi indicated physical presence or materialism as opposed to the emotive elements in the subjectivity of the artist. Wu Guanzhong’s suggestion that formal expression in art, which pointed to individualism and could be independent of the physical world, was a radical opposition to the steadfast social realist value in Cai Yi’s aesthetics.

In The Formal Beauty of Painting, Wu Guanzhong wrote about his training in Paris, how murals rendering medieval, classical, romantic and modern music from the music conservatory were part of the syllabus in his Paris atelier. Students were trained to think of structuring pictorial composition based on the abstract and formal terms of musical rhythm so as to ensure rhythmic flow in each painting. In other words, the subject matter need not be a predominating concern. The rhythmic beauty of lines in harmony to musical tune can be seen in works like Wild Vines with Flowers Like Pearls, (1997), Pines Upon the Yulong Mountains, (1997), and Marriage Ties on the Wall (1999).

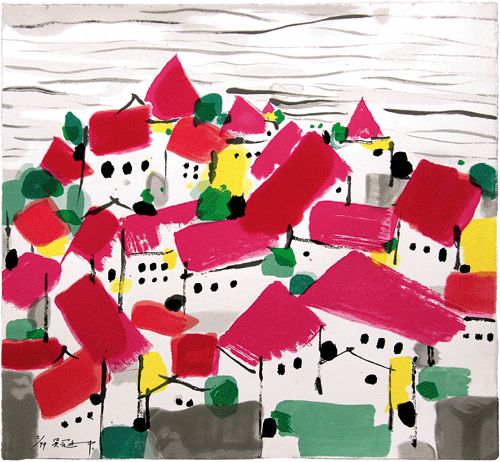

Wu further noted that style had to be located in the feelings of the individual, a radical departure from social realist values in the mid-1940s to mid-1970s. He asserted that formal beauty was the main content of art, that the object being rendered was secondary, a means rather than an end.

Meyer Schapiro wrote in 1953 that style was the constant form in the art of an individual or a group. Wu Guanzhong has spoken of style also very much in this sense of the correlation of form and expression.

The debate on form, however, did not begin only in the 1970s: it was a common concern among early-century Chinese art theorists such as Cai Yuanpei, Lu Xun, Zong Baihua and Deng Yizhe. Zong Baihua regarded beauty and its characteristics as being located in form and rhythm, and what it manifests is the inner core of life and the energy within, the lively and yet orderly movement and zest of life. Deng Yizhe regards art to be the interaction of the subjective emotive and the objective physical, which very aptly describes Wu Guanzhong’s art and creative intent.

In such aesthetic considerations, form must be akin to the concept of sadrsya in Indian art, which does not imply naturalism, but an attempt at true knowledge of an object. To further quote Deng Yizhe, “form emancipates itself from physical constraint and turns to the physics (life) as the object of depiction.” In this regard, Wu Guanzhong is not actually a formalist, if by formalism we mean the physical properties in art that do not subscribe to references beyond themselves, that is, ‘non-objective’ art.

Abstraction and Figuration

It is often said that Wu Guanzhong’s paintings became more ‘abstract’ from the mid-1980s onwards. Considering a progression from The Ruin of Gaochang II (1987), Company (1989), A Dream in the Daytime (1991), Ongoing Years (1992), White Flowers (1993), Zhangjiajie (1997), to In Red and White (2003), there was indeed a greater emphasis on patterns and colours taking centre-stage, sometimes overpowering even the subject of the work. In reading through Wu’s writings, this ‘progression’ did not represent a ‘break’ from figuration to abstraction as such, but were rather the realisations of fundamental aesthetic principles that he held since the early period. Wu concluded that it was up to the painter to choose the subject of the painting.

Such non-dependency on subject matter and the artist’s freedom to inject subjectivity into the physical landscape explains Wu Guanzhong’s trajectory towards ‘abstraction.’ This is seen, for instance, in comparing his paintings ofthe earlier and later periods, in the series of An Osmanthus (1977), Ongoing Years (1992) and Within and Without the Window (2001). Using the term ‘abstraction’, however, is tricky when it comes to looking at Chinese art. Not only are the contrasting notions of abstraction and figuration less pronounced given that Chinese art did not have a parallel history of representational painting in the Renaissance tradition, the problematic issue of representation was conceived differently since the early beginnings of Chinese painting some two millennia ago.

Yi and yijing (‘realm of yi’) are terms frequently used to describe the key characteristics of Chinese art and aesthetics. Etymologically, yi referred to ‘higher-order thought.’ When it comes to art, this higher-order thought can be understood as the interaction of the subjective emotive and the objective physical world. The line was never drawn between figuration and abstraction in the Chinese philosophical tradition.

Audience

In The Formal Beauty of Painting, Wu Guanzhong stressed that art creation is a kind of formal thinking, and that formal beauty is a key link in this. It is through formal creation that an artist eventually develops his own style. Such is the natural result of being true to one’s feelings over a long period of artistic practice. He emphasized that even after formal abstraction, there should still be a connection between the artwork and its source in life.

Wu called his introduction to the catalogue of his 1993 solo exhibition at the Musée Cernuschi in Paris, To the Audience, saying he had dedicated his life to the interfaces of Chinese and western culture. The audience, he said, could tell if there were meaningful insight and depth in any attempt at the integration of cultures.

Given Wu Guanzhong’s magnanimity and deep respect for intercultural values, his broad brushstroke gesture of presenting his largest donation to Singapore is not entirely a surprise. Singapore has come a long way from the days of ‘open sliced pineapples.’ In his usual perceptive way, Wu Guanzhong noted, “Singapore is a country I respect. It is positioned between the east and the west with regards to ethics and quality of life; it is close to China, as it is close to the west; the virtues of both sides are concentrated in you.” Wu then added that Singapore has done well in areas such as transport and economy, but has not given enough emphasis to culture and the arts. Wu Guanzhong’s donation is a “gift for the future,” says Jane Ittogi, chair of Singapore Art Museum. The art of Wu Guanzhong is a gift to humanity, from the decussation of cultures in the 20th century, to the future of the 21st and beyond.

*Original article by Kwok Kian Chow, founding Director of the Singapore Art Museum and Director of the new National Art Gallery of Singapore.

This article is an excerpt from a longer essay written on the occasion of the Wu Guanzhong exhibition at the Shanghai Art Museum, which featured works the artist has generously donated to the Shanghai Art Museum, National Art Museum of China and Singapore Art Museum.